Like the pair of mice in Leo Lionni’s classic children’s book, I had a busy year in 2012. It was a great year, but an exhausting one.

The year began last January with a surprise: I was mentioned by Stanley Fish in an anti-digital humanities screed in the New York Times. That’s something I can check off my bucket list. (By the way, my response to Fish fit inside a tweet.) Ironically, had Fish read my chapter in Debates in the Digital Humanities, which was published the very same week, he might have seen some strange correspondences between his stance toward the digital humanities and my own. This chapter, “Unseen and Unremarked On: Don DeLillo and the Failure of the Digital Humanities,” has recently become open-access, along with the rest of the book. Hats off to Matt Gold, the Debates editor, as well as his crew at the Graduate Center at CUNY and the University of Minnesota Press for making the book possible in the first place, and open and online in the second place.

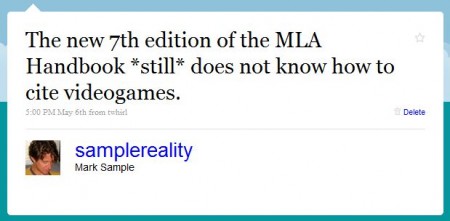

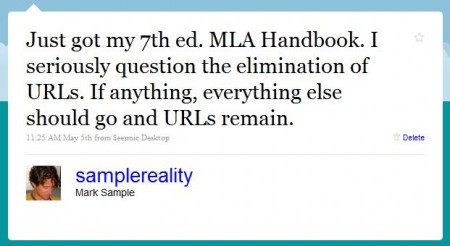

In January I also performed my first public reading of one of my creative works— Takei, George—during the off-site electronic literature reading at the 2012 MLA Convention in Seattle. There’s even grainy documentary footage of this reading, thanks to the efforts of the organizers Dene Grigar, Lori Emerson, and Kathi Inmans Berens. I also gave a well-received talk at the MLA about another work of electronic literature, Erik Loyer’s beautiful Strange Rain. And finally in January, I spent odd moments at the convention huddled in a coffee shop (this was Seattle, after all) working with my co-authors on the final revisions of a book manuscript. More about that book later in this post.

All of this happened in the first weeks of January. And the rest of the year was equally as busy. In addition to my regular commuting life, I traveled a great deal to conferences and other gatherings. As I mentioned, I presented at the MLA, but I also talked at the Society for Cinema and Media Studies convention (Boston in March), Computers and Writing (Raleigh in May), the Electronic Literature Organization (Morgantown in June), and the Society for Literature, Science, and the Arts (Milwaukee in September). In May I was a co-organizer of THATCamp Piedmont, held on the campus of Davidson College. During the summer I was a guest at the annual Microsoft Research Faculty Summit (Redmond in July). In the fall I was an invited panelist for my own institution’s Forum on the Future of Higher Education (in October) and an invited speaker for the University of Kansas’s Digital Humanities seminar (in November).

If the year began the publication of a modest—and frankly, immensely fun to write—chapter in an edited book, then I have to point out that it ended with the publication of a much larger (and challenging and unwieldy) project, a co-authored book from MIT Press: 10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1));: GOTO 10 (or 10 PRINT, as we call it). I’ve already written about the book, and I expect more posts will follow. I’ll simply say now that my co-authors and I are grateful for and astonished by its bestselling (as far as academic books go) status: within days of its release, the book was ranked #1,375 on Amazon, out of 8 million books. This figure is all the most astounding when you consider that we released a free PDF version of the book on the same day as its publication. More evidence that giving away things is the best way to also sell things.

I was busy with other scholarly projects throughout 2012 as well. I finished revisions of a critical code studies essay that will appear in the next issue of Digital Humanities Quarterly, and I wrapped up a chapter for an edited collection coming out from Routledge on mobile media narratives. I also continued to publish in unconventional but peer-reviewed venues. Most notably, Enculturation and the Journal of Digital Humanities, which has published two pieces of mine. On the flip side of peer-review, I read and wrote reader’s reports for several journals and publishers, including University of Minnesota Press, MIT Press, Routledge, and Digital Humanities Quarterly. (You see how the system works: once you publish with a press it’s not long until they ask you to review someone else’s work for them. Review it forward, I say.)

In addition to scholarly work, I’ve invested more time than ever this year in creative work. On the surface my creative work is a marginal activity—and often marginalized when it comes time to count in my annual faculty report. But I increasingly see my creativity and scholarship bound up in a virtuous circle. I’ve already mentioned my first fully-functional work of electronic literature, “Takei, George.” In June this piece appeared as a juried selection in Electrifying Literature: Affordances and Constraints, a media art exhibit held in conjunction with the 2012 Electronic Literature Organization conference. A tip to other scholars who aim to do more creative work: submit your work to juried exhibitions or other curated shows; if your work is selected, it’s the equivalent of peer-review and your creative work suddenly passes the threshold needed to appear on CVs and faculty activity reports. Another creative project of mine, Postcard for Artisanal Tweeting, appeared in Rough Cuts: Media and Design in Process, an online exhibit curated by Kari Kraus on The New Everyday, a Media Commons Project.

My own blog is another site where I blend creativity and scholarship. My recent post on Intrusive Scaffolding is as much a creative nonfiction piece as it is scholarship (more so, in fact). And my favorite post of 2012 began as an inside joke about scholarly blogs. The background is this: during a department meeting discussion about how blogging should be recognized in our annual infrequent merit salary raises, a senior colleague expressed concern that one professor’s cupcake blog would count as much as another professor’s research-oriented blog. In response to this discussion, I wrote a blog post about cupcakes that blended critical theory and creativity. And cursing. The post struck a nerve, and it was my most widely read and retweeted blog post ever. About cupcakes.

Late in 2012 my creative work took me into new territory: Twitterbots, those autonomous “agents” on Twitter that are occasionally useful and often annoying. My bot Citizen Canned is in the process of tweeting every unique word from the script of Citizen Kane, by order of frequency (as opposed to, say, by order of significance, which would have a certain two syllable word appear first). With roughly 4,400 unique words to tweet, at a rate of once per hour, I estimate that Citizen Kane will tweet the least frequently used word in the movie sometime five months from now.Another of the Twitterbots I built in 2012 is 10print_ebooks. This bot mashes up the complete text of my 10 PRINT book and generates occasionally nonsensical but often genius Markov chain tweets from it. The bot also incorporates text from other tweets that use the #10print hashtag, meaning it “learns” from the community. The Citizen Cane bot runs in PHP while the 10 PRINT bot is built in Processing.

Alongside this constant scholarly and creative work (not to mention teaching) ran a parallel timeline, mostly invisible. This was me, waiting for my tenure decision to be handed down. In the summer of 2011 I submitted my materials and by December 2011, I learned that my department had voted unanimously in my favor. Next, in January 2012 the college RPT (Rank-Promotion-Tenure) committee voted 10-2 in my favor. It’s a bit crazy that the committee report echoes what I’ve heard about my work since grade school:

In February my dean voted in favor of my case too. Next came the provost’s support at the end of March. In a surprise move, the provost recommended me for tenure on two counts: genuine excellence in teaching and genuine excellence in research. Professors usually earn tenure on the strength of their research alone. It’s uncommon to earn tenure at Mason on excellence in teaching, and an anomaly to earn tenure for both. By this point, approval from the president and the Board of Visitors (our equivalent of a Board of Trustees) might have seemed like rubber stamps, but I wasn’t celebrating tenure as a done deal. In fact, when I finally received the official notice—and contract—in June, I still didn’t feel like celebrating. And by the time my tenure and promotion went into effect in August 2012, I was too busy gearing up for the semester (and indexing 10 PRINT) to think much about it.

In other words, I reached the end of 2012 without celebrating some of its best moments. On the other hand, I feel that most of its “best moments” were actually single instances in ongoing processes, and those processes are never truly over. 10 PRINT may be out, but I’m already looking forward to future collaborations with some of my co-authors. I wrote a great deal in 2012, but much of that occurred serially in places like ProfHacker, Play the Past, and Media Commons, where I will continue to write in 2013 and beyond.

What else with 2013 bring? I am working on two new creative projects and I have begun sketching out a new book project as well. Next fall I will begin a year-long study leave (Fall 2013/Spring 2014), and I aim to make significant progress on my book during that time. Who knows what else 2013 will bring. Maybe sleep?

[Header image: A Busy Year by Leo Lionni]

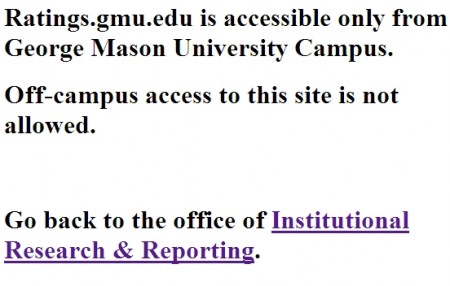

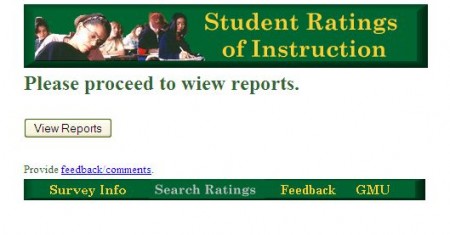

To be fair, I’m hoping that the typo has been corrected since I captured this screen shot in May. But I wouldn’t know for sure. You see, it’s August and I’m off-campus right now, as are most faculty and students, and I can’t even electronically access my own teaching evaluations, let alone those of other professors, unless I’m physically there.

To be fair, I’m hoping that the typo has been corrected since I captured this screen shot in May. But I wouldn’t know for sure. You see, it’s August and I’m off-campus right now, as are most faculty and students, and I can’t even electronically access my own teaching evaluations, let alone those of other professors, unless I’m physically there.