On Thursday, January 5, I participated on a round table at the 2023 MLA convention, organized by the MLA itself. The panel was called “Infrastructures of Professional Development.” Here’s the panel description:

This roundtable includes leaders who have developed technical, pedagogical, administrative, and organizational structures with potential to serve as sites for professional development. Brief comments will be followed by an open forum on how the MLA can learn from and collaborate with these leaders and others to grow and enhance professional development offerings in service to members across the career arc.

I was joined by Kathleen Fitzpatrick and Sonja Rae Fritzsche, both from Michigan State University. We each delivered short remarks and the proceeded to have a wide-ranging discussion. Here are my prepared comments, such as they were.

➰➰➰

I appreciate the work that Jason Rhody and Janine Utell at the MLA have done to bring this group of panelists together. My opening comments are going to be brief, because I know the best part of these roundtables is the discussion that follows. There are four points I want to make today regarding “Infrastructures of Professional Development.” And I want to preface them by saying that I’m zooming out and offering broad generalizations here, rather than nuts-and-bolts details about professional development initiatives that I’ve been a part of or helped to build—though I’m happy to talk about those in the discussion. The reason I’m zooming out is because my own context—I’m at a relatively well-resourced small liberal arts college—may not be your context, and infrastructure, as well as what counts as professional development, is highly contextual.

I.

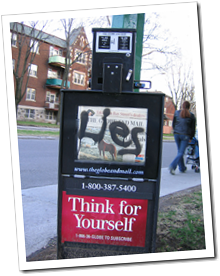

I want to call your attention to the word infrastructures in our panel title. It’s an odd word in this context. You hear infrastructure and you think roads, bridges, sewer lines, power substations. The underlying structures that make everything else possible. As Susan Leigh Star and Martha Lampland put it, infrastructure is “the thing other things ‘run on’” (Star and Lampland 17). And the funny thing about infrastructures—and I’m far from the first person to point this out—is that when they are working, you don’t think about them. They’re all but invisible. It’s when infrastructure breaks down that it becomes visible, or as Heidegger would put it (and forgive me for quoting Heidegger), they become “present-at-hand.” They are no longer transparent. They’re in your face. You don’t notice the road until there’s a pothole. You don’t pay attention to a bridge until it’s closed and you have to detour the long way around. You don’t think about the power until the lights don’t come on.

II.

Let’s think about two phase states of infrastructure when it comes to professional development. The first phase state: infrastructure when it works and is invisible; and the second phase state: infrastructure when it’s not working and very much visible. It presents a bit of a dilemma. Infrastructures for professional development, if they’re working well, you don’t even see them. You take them for granted. It makes professional development hard to talk about, to share ideas with others, to build on what’s working at other institutions or organizations. That sharing is one of the things I hope we get to do today.

The flip side occurs when the processes for professional development aren’t working—and I’m sure we all have war stories to trade. The infrastructure becomes visible, because it’s broken. But what’s needed to fix or repair or replace that infrastructure—we might call this speculative infrastructures—those possibilities remain out of sight. And in fact, discussion about speculative infrastructures is displaced by something else. I’m thinking of a dynamic that Sara Ahmed describes frequently in her work. When someone points out a problem, they become the problem, not the problem itself. Working in institutions, as many of us do, you’ve seen this. As Ahmed puts it in her “Feminist Killjoys” essay, when you are the one to point out a problem, it means “you have created a problem. You become the problem you create” (“Feminist Killjoys (And Other Willful Subjects)”). It’s almost as if the problem didn’t exist—or at least some people wanted to pretend it didn’t exist—until somebody pointed out the problem. So I think our challenge here, in addition to sharing infrastructures for professional development that are promising, is to diagnose infrastructures for professional development in a way in which our complaints don’t supersede the underlying problem. Ahmed’s latest book, Complaint!, is instructive here, especially since it’s centered on institutions. Ahmed observes that we often think about complaints as formal allegations—I lodged a complaint—but she shows how complaints are “an expression of grief, pain, or dissatisfaction, something that is a cause of a protest or outcry, a bodily ailment” (Complaint! 4). There is an affective and embodied dimension to complaints. So as we talk this afternoon, and if some complaints about institutions and organizations come up, let’s hear the complaints for what they really are, testimonies about our lived experiences.

III.

As a consequence of infrastructure often being invisible, the people who design, implement, and maintain those infrastructures remain invisible as well. This is true whether the infrastructure is a bridge or an online collective. If we think about, say, the work the MLA does to support professional development, most members of the MLA do not know who is actually doing that work to support professional development. Who are the faces? What are their names? We have Jason and Janine here, but most MLA members would be hard pressed to name the people, beyond Paula, who work to make the convention happen. And to be clear, the convention, whatever else it is, is an infrastructure for professional development. And if this were any other infrastructure, that invisibility would be something you’d want. If you don’t know the people making something work, if they can fade into the background while the thing functions seamlessly, that’s usually what you want. It means things are working. But, in my own subfields of digital humanities, media studies, and science and technology studies, there’s been a growing attention paid to the labor of people who make things, who make things run, and who fix the things when they’re broken. And this is something I think we in our respective institutions and organizations should consider when it comes to infrastructures for professional development. Not just, as I’m doing here, recognizing the work that everyone is putting in to provide opportunities for professional development, but actually putting forward the stories and aspirations of those of you, of us, who work on infrastructures that support professional development. In other words, step out from behind the curtain, and introduce ourselves to our constituents. Tell them our stories—your stories. What are our hopes and dreams, what do we get out of supporting you? Show how supporting professional development isn’t simply a transaction, but, it’s a relationship. Make it clear that whatever infrastructure you are providing is like Soylent Green, it’s made out of people.

IV.

This brings me to my fourth and final point. People. One of the lodestars for how I think about labor in the academy is Miriam Posner, at UCLA. Years ago Miriam wrote a blog post that I still think about all the time. The post is called “Commit to DH People, Not DH Projects.” Miriam is talking here specifically about the digital humanities, and critiquing the tendency to frame work in DH around projects. What if, she wonders, we put the emphasis on people, not projects? Let me quote her here: “What if,” Miriam writes, “we viewed digital methods as a contribution to the long arc of a scholar’s intellectual development, rather than tools we pick up in the service of an immediately tangible product? Perhaps we’d come up with better ways of investing in people’s long-term potential as scholars” (Posner). If we blur out the particulars of digital humanities scholarship here, and think more broadly about Miriam’s underlying point, it applies in so many ways to supporting professional development across the board, whether that development is focused on scholarly, pedagogical, creative, or even administrative pursuits. The infrastructures for professional development need to support people, not projects, not stages of their careers. People, not one-off workshops, not a conference here or there, not week-long institutes, not webinars. People, and people over a long period of time, people who evolve and grow over time. Professional development, in the end, is about people supporting people, people supporting each other.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. Complaint! Duke University Press, 2021.

—. “Feminist Killjoys (And Other Willful Subjects).” The Scholar and Feminist Online, vol. 8, no. 3, Summer 2010, http://sfonline.barnard.edu/polyphonic/print_ahmed.htm.

Posner, Miriam. “Commit to DH People, Not DH Projects.” Miriam Posner’s Blog: Digital Humanities, Data, Labor, and Information, 18 Mar. 2014, https://miriamposner.com/blog/commit-to-dh-people-not-dh-projects/.

Star, Susan Leigh, and Martha Lampland, editors. Standard and Their Stories: How Quantifying, Classifying and Formalizing Practices Shape Everyday Life. Cornell University Press, 2009.