This is the first academic semester in which students have been using the revised 7th edition of the MLA Handbook (you know, that painfully organized book that prescribes the proper citation method for material like “an article in a microform collection of articles”).

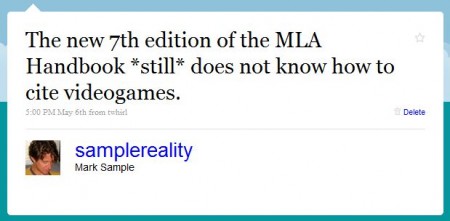

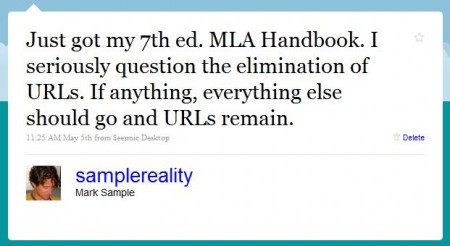

From the moment I got my copy of the handbook in May 2009, I have been skeptical of some of the “features” of the new guidelines, and I began voicing my concerns on Twitter:

But not only does the MLA seem unprepared for the new texts we in the humanities study, the association actually took a step backward when it comes to locating, citing, and cataloging digital resources. According to the new rules, URLs are gone, no longer “needed” in citations. How could one not see that these new guidelines were remarkably misguided?

To the many incredulous readers on Twitter who were likewise confused by the MLA’s insistence that URLs no longer matter, I responded, “I guess they think Google is a fine replacement.” Sure, e-journal articles can have cumbersome web addresses, three lines long, but as I argued at the time, “If there’s a persistent URL, cite it.”

Now, after reading a batch of undergraduate final papers that used the MLA’s new citation guidelines, I have to say that I hate them even more than I thought I would. Although “hate” isn’t quite the right word, because that verb implies a subjective reaction. In truth, objectively speaking, the new MLA system fails.

The MLA apparently believes that all texts are the same

In a strange move for a group of people who devote their lives to studying the unique properties of printed words and images, the Modern Language Association apparently believes that all texts are the same. That it doesn’t matter what digital archive or website a specific document came from. All that is necessary is to declare “Web” in the citation, and everyone will know exactly which version of which document you’re talking about, not to mention any relevant paratextual material surrounding the document, such as banner ads, comments, pingbacks, and so on.

The MLA turns out to be extremely shortsighted in its efforts to think “digitally.” The outwardly same document (same title, same author) may in fact be very different depending upon its source. Anyone working with text archives (think back to the days of FAQs on Gopher) knows that there can be multiple variations of the same “document.” (And I won’t even mention old timey archives like the Short Title Catalogue, where the same 15th century title may in fact reflect several different versions.)

The MLA’s new guidelines efface these nuances, suggesting that the contexts of an archive are irrelevant. It’s the Ghost of New Criticism, a war of words upon history, “simplification” in the name of historiographic homicide.

Agreed and agreed again, Mark – and I’ll add, as well, the frustration of trying to cite specific pages within a poorly managed site, wherein all the pages have the same title (i.e., the title of the front page, presumably copied over in the metadata of the template used for new pages). So it’s not just different versions of the same document that are effaced; in this case, it’s entirely different documents that all inconveniently called the same thing. Only the URL distinguishes.

And honestly, if the primary concern is long URLs within scholarly databases, that’s probably a red herring: in many cases, these long citations aren’t persistent URLs at all, but rather search histories that don’t even function once the browser is closed. JStor manages to get their direct links down to only 34 characters, including the http://.

Indeed — so many issues that seem to defy the fundamental aspect of a citation: help the reader to find the same resource used. I’ve been fretting about this since I saw your tweet, which I plan to misquote and misrepresent willy-nilly in papers, since without providing an URL there is no way to find it again to confirm or refute my reading of it!

For teachers, this will put a huge practical hurdle on checking how students are reading a source. I used to spend a fair amount of time checking students use of sources in beginning writing courses. Adding the hurdle of hunting via search engines will only slow and discourage that pedagogical step. Worse, students already have a hard time with keeping different documents distinct in their minds — a crucial first step to being able to work with the relationships between documents. The URLs are a helpful step in doing that.

For researchers, similar issues — if I read a citation, I want to get there quickly and see the surrounding material. This hurts the useful technique of going through others bibliographies to find sources.

And more to the paratextual stuff, we do a huge amount of republishing posts via RSS/Atom in UMWBlogs, but one twist is that the same document at two URLs doesn’t merge the comments — there’s a completely different set of comments for each URL. That makes a completely different contextualization and probably interpretation for the two resources, though they are supposedly the same document. The issue only gets worse for things like a Flickr image or YouTube video that’s also discussed in a blog post. Knowing whether someone was working from the image or video in Flickr/YouTube/whatever — surrounded by a pool, or a channel, or a photostream, etc. — as opposed to the post providing a completely different context makes a huge difference.

Last, just to really get my geek on, I’ve spent a lot of time writing code to mine out data, and URLs are relatively easy to regex out of a paper in digital form. So much for that!

Not to mention that many of the publishers I know are desperately trying to move to an electronic platform; one of the things that will distinguish e-books from print books is the possibility of making an e-book a “networked object.” One of the very easiest things to do with regard to putting a book online (not that it’s very easy) would be to link every reference to a citation record of some kind (an Open Library catalog record, for instance, or to a DOI or PURL). Authors are just going to have to get used to putting URLs in again in a few years. Maybe the MLA is just trying to keep itself in the style guide edition business.

It’s always helpful for us at the MLA to hear from researchers about how MLA style suits their needs. The seventh edition of the MLA Handbook is in fact the product of extensive consultations with users — scholars, librarians, instructors, and students.

These consultations made it clear that users of the handbook have a wide range of needs. Hence, the MLA guidelines are designed to be practical for general writers while leaving openings for specialists.

Our guidelines call for elements that are both common to many sources and likely to provide enduring assistance to readers who seek the sources. Testing the URLs in the examples in previous editions, we found that most were obsolete. Moreover, our advisers noted that requiring URLs placed a burden on writers. For many writers, distinguishing permanent URLs from nonpermanent ones is a challenge. Others are not conversant with copying and pasting URLs and so type them, with the attendant risk of typos. A widely used documentation style must serve researchers at all levels.

Contrary to Mark Sample, this does not mean the MLA believes “it doesn’t matter what digital archive or website a specific document came from.” Our guidelines call for naming the archive or Web site.

We recognize that some instructors and publishers find URLs valuable, so the handbook gives instructions for recording them (5.6.1). If you’re comparing different versions of a single work on the Web, you probably will want to take advantage of the flexibility of MLA style and add URLs or other data.

The rise of e-books will indeed increase the networking capacity of citations. At this point, though, it seems that publishers, not authors, are the most likely to add DOIs or similar metadata to published citations. We will add guidelines for this practice as it becomes more common.

We welcome further comments. So that we’re sure to have them on hand for preparing the next edition, please send them directly to me (execdirector@mla.org).

Rosemary G. Feal, Executive Director

MLA

I have to say, when I cracked open to new MLA handbook, I checked if there were guidelines for citing tweets. Something for the eighth edition?

Another thing to think about is static versus dynamic content, and all the other stuff on the Deep Web (which I’m guessing the MLA has taken into consideration). URL plus access date makes a lot more sense if you’re dealing with static html, but not so much for dynamic content like Twitter feeds. Linking to http://www.twitter.com/mlaconvention for Rosemary Feal’s tweet that got me here won’t help you much in twelve months! I know there’s a way to make a permalink for individual tweets, but I’m fairly computer literate, and I had to do some googling to figure out how to get that link (click on the time posted link, btw)–so, not very convenient to find out how to get permalinks for all your web sources, even assuming that there is a way (and most of the time, there isn’t), and assuming that you’re advanced in google-fu.

And in practice, even if I see a JSTOR permalink, Im still going to access that article with the other author/title/journal info rather than typing in a bunch of numbers.

All of which is to say… isnt thinking that providing a URL gives access to a stable text a way of wishing away différance?

[…] a Comment Let us pause, for a moment, to consider the wisdom we might glean from Twitter. Or, as Mark Sample puts it: The new 7th edition of the MLA Handbook *still* does not know how to cite […]

[…] 22, 2009 Let us pause, for a moment, to consider the wisdom we might glean from Twitter. Or, as Mark Sample puts it: The new 7th edition of the MLA Handbook *still* does not know how to cite […]

I appreciate everyone’s questions and comments. Thanks, too, Rosemary, for providing some background on the new MLA style guidelines. The overarching problem, of course, is that our research practices cannot keep up with the evolving forms we study and incorporate into our work. Every other major citation format is facing similar challenges.

I’m not so concerned with e-journals or e-books; the standard publication info will almost always make these scholarly sources easy to find. It’s the orphan items, the born-digital primary source material with no print precedent that are most at risk for being citationally (not to mention materially) lost. There might be dozens of YouTube videos all with the same name and date (say, a short video of a street protest), but each video might be different. The only specific indicator in this case is the URL. Expert scholars may instinctively include the URL in a citation, but I fear the nuances will be lost among undergraduates and even graduate students (especially if they use something like Endnote or Zotero to auto-generate citations).

The problem of disappearing URLs and non-persistent web addresses is a serious one. But rather than resigning ourselves to the web’s impermanence, we should see this as a research opportunity. I’d argue that even if we know for certain that a URL will soon change or disappear, it is regardless a key component of that document’s metadata. Art history uses the term provenance to describe an object’s ownership history, its physical relations as it has passed hands, both legitimately and otherwise, through time and space. Until everything has a persistent DOI or URI, the URL is the best way to establish the provenance of digital materials.

I’ve always found that the requirements of the various citation styles tend to be behind the times. It’s a good argument for a community-administrated citation style. Imagine the advantage to a Wikipedia-style approach to developing citations, where the editors/administrators are academics such as yourself.

The reality is that information changes fast, too fast for a staid IRL committee to keep up and still provide effective guidelines for the resources that students and researchers access daily. At the same time, the intersections of tech and text open up serious possibilities. For example, if part of the issue is the length of a URL within a text citation, why not use shortened links?

The other opportunity comes in the form of link bookmarking services like Diigo, which allow users to cache a web page. This bypasses the issue of non-persistent web addresses, research disappearing behind paywalls, etc… I often use it when writing blog posts. Instead of linking to the original article, I’ll link to the cached page.

Like I said, all this provides a good argument to resist the imposition of aged and inefficient citation rules and the formation of something unique and up to date that optimizes citation technique for compatibility with the latest technology by using the latest technology.

[…] his blog post on the subject, “The Modern Language Association Wishes Away Digital Différance”, Sample clearly articulates the issues at stake (as usual): In a strange move for a group of people […]

[…] linking to you in comments. Nice, new service. It also offers a WordPress plugin that allows you to embed twitter comments in a post’s comment thread (link is an example of it […]

[…] Lastly, DeVoss and Rosati#8217;s article reminded me of the latest (7th ed.) MLA Handbook, which now tells us new ways of citing online documents, links, etc., but is so short-sighted in its efforts that it erases differences among texts. Moreover, in putting out this new edition, the MLA is assuming that scholars have the digital literary skills to navigate and do research in the online world. What we need is a supplementary handbook that teaches us, in addition to the mere citing of sources, the how we should find and evaluate digital sources, and why and when we should cite them. Mark Sample wrote an intriguing and useful blog post on the MLA#8217;s 7th ed.: The Modern Language Association Wishes Away Digital Differance. […]