I quit Twitter.

Or, more accurately, I quit twittering. Nearly three weeks ago with no warning to myself or others, I stopped posting on Twitter. I stopped updating Facebook, stopped checking in on Gowalla, stopped being present. I went underground, as far underground as somebody whose whole life is online can go underground.

In three years I had racked up nearly 9,000 tweets. If Twitter were a drug, I’d be diagnosed as a heavy user, posting dozens of times a day. And then I stopped.

Most people probably didn’t notice. A few did. I know that they noticed because my break from social media wasn’t complete. I lurked, intently, in all of these virtual places, most intently on Twitter.

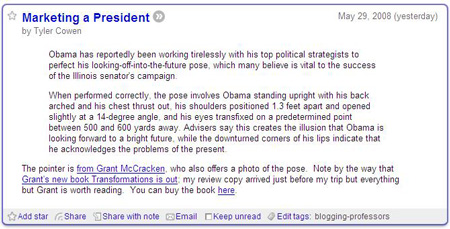

In the weeks I was silent on Twitter I read in my timeline about divorce, disease, death. I read hundreds of tweets about nothing at all. I read tweets about scholarship, about teaching, about grading, about sleeping and not sleeping. Tweets about eating. Tweets about me. Tweets with questions and tweets with answers. And I thought about how I use Twitter, what it means to me, what it means to share my triumphs and my frustrations, my snark and my occasional kindness, my experiments with Twitter itself.

For the longest time the mantra “Blog to reflect, Tweet to connect” was how I thought about Twitter. The origin of that slogan is blogger Barbara Ganley, who was quoted two years ago in a New York Times article on slow blogging. Ganley’s pithy analysis seemed to summarize the difference between blogging and Twitter, and it circulated widely among my friends in the digital humanities. I repeated the slogan myself, even arguing that Twitter was the back channel for the digital humanities, an informal network—the informal network—that connected the graduate students, researchers, teachers, programmers, journalists, librarians, and archivists who work where technology and the humanities meet.

My retreat from Twitter has convinced me, however, that Twitter is not about connections. Saying that you tweet in order to connect is like saying you fly on airplanes in order to get pat-down by the TSA. If you’re looking for connections on Twitter, then you’re in the wrong place. And any connections you do happen to form will be random, accidental, haunted by mixed signals and potential humiliations.

I’ve been mulling over a different slogan in my mind. One that captures the multiplicity of Twitter. One that acknowledges the dynamism of Twitter. One that better describes my own antagonistic use of the platform. And it’s this:

Blogging is working through. Twitter is acting out.

Twitter is not about connections. Twitter is about acting out.

I mean “working through” and “acting out” in several ways. There’s the obvious allusion to Freud: working through and acting out roughly correspond to Freud’s distinction between mourning and melancholy. A mourner works through the past, absorbs it, integrates it. A mourner will think about the past, but live into the present. The melancholic meanwhile is prone to repetition, revisiting the same traumatic memory, replaying variations of it over and over. The melancholic lashes out, sometimes aggressively, sometimes defensively, often unknowingly.

It’s not difficult to see my use of Twitter as acting out, as rehashing my obsessions and dwelling upon my contentions. Even my break from Twitter is a kind of acting out, a passive-aggressive refusal to play.

But I also mean “acting out” in a more theatrical sense. Acting. Twitter is a performance. On my blog I have readers. But on Twitter I have an audience.

To be sure, it’s a participatory audience. Or at least possibly participatory. And this leads me to another realization about Twitter:

Twitter is a Happening.

I’m using Happening in the sixties New York City art scene sense of the word: an essentially spontaneous artistic event that stands outside—or explodes from within—the formal spaces where creativity is typically safely consumed. Galleries, stages, museums. As Allan Kaprow, one of the founders of the movement, put it in 1961,

[quote]Happenings are events that, put simply, happen. Though the best of them have a decided impact—that is, we feel, “here is something important”—they appear to go nowhere and do not make any particular literary point.[/quote]

Happenings lack any clear divide between the audience and the performers. Happenings are emergent, generated from the flimsiest of intentions. Happenings cannot be measured in terms of success, because even when they go wrong, they have gone right. Chance reigns supreme, and if a Happening can be reproduced, reenacted, it is no longer a happening. And if it’s not a Happening, then nothing happened.

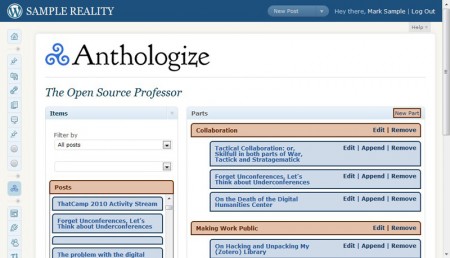

Whether it’s a Twitter-only mock conference, ridiculous fake direct messages, or absurd tips making fun of our professional tendencies, I have insisted time and time again—though without consciously framing it this way—that Twitter ought to be a space for Happenings.

If you’re not involved somehow in a Twitter Happening—if you’re not inching toward participating in some spontaneous communal outburst of analysis or creativity—then you might as well switch to Facebook for making your connections.

Because Twitter is a Happening that thrives on participation, there’s something else I’ve realized about Twitter:

Twitter is better when I’m tweeting.

If you are one of the nearly four hundred people I follow, don’t take this the wrong way, but Twitter is better when I’m around. I don’t mean to say that the rest of you are uninteresting. But until I or a few other like-minded people in my Twitter stream do something unexpected, Twitter feels flat, a polite conversation that may well be informative but is nothing that will leave me wondering at the end of the day, what the hell just happened?

If you are one of the nearly four hundred people I follow, don’t take this the wrong way, but Twitter is better when I’m around. I don’t mean to say that the rest of you are uninteresting. But until I or a few other like-minded people in my Twitter stream do something unexpected, Twitter feels flat, a polite conversation that may well be informative but is nothing that will leave me wondering at the end of the day, what the hell just happened?

I suppose this sounds arrogant. “Twitter is better when I’m around”?? I mean, who on earth made me judge of all of Twitterdom?? And indeed, this entire blog post likely seems self-indulgent. But I didn’t write it for you. I wrote it for me. I’m working through here. And besides, I’ve been criticized too many times by the people who know me best in real life, criticized for being too modest, too eager to downplay my own voice, that I’ll risk this one time sounding self-important.

There’s one final realization I’ve had about Twitter. For a while I had been wondering whether every word I wrote on Twitter was one less word I would write somewhere else. Was Twitter distracting me from what I really needed to write? Was Twitter making me less prolific? And so here it is, my most coherent articulation of what led me to break suddenly from social media: I quit Twitter because I wished to write deliberately, to type only the essential words of my research, and see if I could not learn what Twitterless life had to teach, and not, when I came up for tenure, discover that I had not written at all.

There’s one final realization I’ve had about Twitter. For a while I had been wondering whether every word I wrote on Twitter was one less word I would write somewhere else. Was Twitter distracting me from what I really needed to write? Was Twitter making me less prolific? And so here it is, my most coherent articulation of what led me to break suddenly from social media: I quit Twitter because I wished to write deliberately, to type only the essential words of my research, and see if I could not learn what Twitterless life had to teach, and not, when I came up for tenure, discover that I had not written at all.

Or something like that.

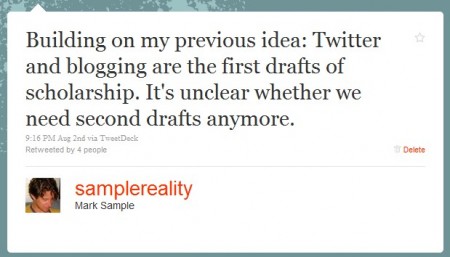

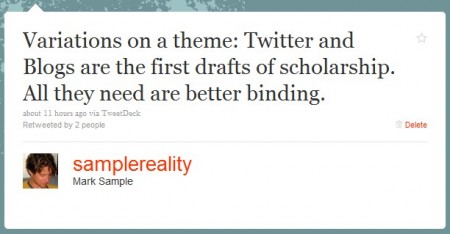

It only took a few days before I knew the answer to my question about Twitter and writing. And it’s this: writing is not a zero sum game.

I write more when I tweet.

This is not as self-evident a truth as it sounds. Obviously every tweet means I’ve written everything I’ve ever written in my life, plus that one additional tweet. So yes, by tweeting I have written more. But in fact I write more of everything when I tweet. I have learned in the past few weeks that Twitter is a multiplier. Twitter is generative. Twitter is an engine of words, and when I tweet, all my writing, offline and on, private and public, benefits. There’s more of it, and it’s better.

And so I am returning to Twitter. While I had experimented with tweeterish postcards during my break from Twitter—what you might call slow tweeting—I am back on Twitter, and back for good. Twitter is a Happening. It’s not a space for connections, it’s a space for composition. I invite you to unfollow me if you think differently, for I can promise nothing about what I will or will not tweet and with what frequency these tweets will or will not come. I would also invite you to the Happening on Twitter, but that invitation is not mine to extend. It belongs to no one and to everyone. It belongs to the crowd.