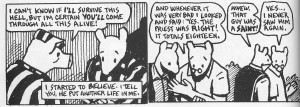

Sandman is a series where death is frequent, horrifying, casual, shocking, and yet strangely benevolent. The obsession with the event or action of dying begins in the very first issue, “Sleep of the Just,” in which selfish magicians attempt to capture “Lord Death” – rather humorously believing that Death is both capturable and male.

Dream, rather irked after his seventy-year captivity, politely informs his gaolers that they should “…count yourself lucky for the sake of your species and your petty planet that you did NOT succeed…that instead you snared Death’s younger BROTHER” (49). Such a forboding connotation attached to D/death seems confirmed by the next arc, in which the demented Dr. Dee casually, horrifically, and frequently murders many, many people, only to be stopped by his own greed (and perhaps Dream’s cleverness – an ambiguity taken up in the final arc of the series, The Kindly Ones).

And yet, when Death first appears, live and in person instead of the fearsome reputation, she is but a chalk-skinned, wild shock of black haired, ankh-wearing girl, seemingly in her late teens or early twenties. Her body language is casual, and she frequently smiles. Though she angrily informs her brother that he is and idiot for trying to solve his problem alone, her temper stems from her deep love for him.

All in all, a rather interesting portrait of the anthropomorphic personification of Death.

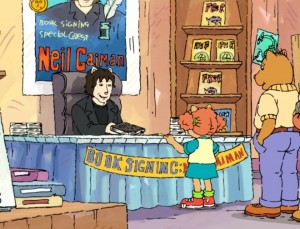

Terry Pratchett, collaborator and friend of Gaiman, created a similar conceptualization of Death, sticking to the traditional image of Death as a skeleton on a pale white (bony) horse (though named Binky). Like Gaiman, however, Pratchett’s death displays intense care for those under his care – often battling against the forces of indifference, bureaucracy, and auditing for the value of the small, the useless, and the chaotic – in other words, for the value of life and meaning.

Which brings up a fascinating point: Gaiman’s death, for all her engaging personality (easily one of the most winsome characters in all literature, in this particular work sharing that title with her sister Delirium and the crow Matthew, both introduced in later volumes) remains a supporting character. Is there something about the nature of a perfectly content, perfectly self-sufficient, happy character that makes them unsuited for a story’s central figure? Though I find Dream an incredibly sympathetic character (an uncommon experience, apparently – I do tend to enjoy the duty-driven, introverted, complicated, emotionally stunted yet intense characters), I find myself intrigued by and yet unable to envision a “Reaper” comic. I doubt Death has a lack of conflict – after all, despite the way all her meetings end with acceptance in “The Sound of Her Wings,” I’ve no doubt some people refuse to accept her comfort. Not to mention the foolish magi who attempt to capture her. But what would Death learn? Unlike Dream, she has already changed significantly (as revealed in the short story volume of the Sandman series, she was originally an arrogant, detached character). An intriguing possibility.

In hindsight, Death’s being perfectly suited for her job may be why Dream gave his tormentors his ominous warning – without someone to take loving charge of the souls of the departed, the world would either fall into everliving destruction, or the agony of lost souls would throw the world’s happiness completely away. I’m inclined to think the latter is the case, since Dream and Death’s brother Destruction forsook his job, and the forces of Destruction continue without him. But in either case, Gaiman argues (along with Pratchett) that our conceptions, our stories we make about ideas (for what is an anthropomoriphic personification based on collective consciousness/belief but an elaborate metaphor or story?) are what make life worth living, and in the end, dying.

In conversations, some people have mentioned that the artwork seems less important in this story than in Watchmen or The Dark Knight. I’d disagree – without the varied yet centrally consistent interpretations of Death, she’d merely be interesting, perhaps slightly amusing. But with her extravagant hand gestures, her casual body posture, mobile features, and distinctive coloring, I think she wouldn’t be the indelibly, incredibly winsome character Gaiman and his collaborators finally created (despite the significantly varied quality of the artists who contributed to the series).