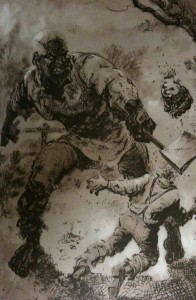

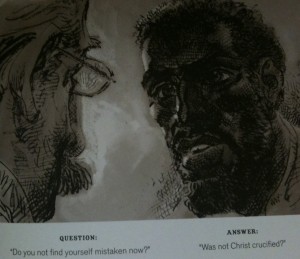

It’s difficult for me to think about war reporting without Michael Herr’s Dispatches quickly coming to mind. Seeing as Herr’s account of Vietnam inspired elements of Full Metal Jacket and Apocalypse Now, and that Herr helped write the screenplays for both films, it’s not difficult to see how my fondness for Dispatches played against “Shooting War.” Where Herr’s Dispatches viscerally displays the horrors of war, with the author himself changed by the events he lives through, Jimmy Burns’ emotional register seems rather limited — he sometimes looks scared, looks bored a lot, drinks a bit, shoots off a few snarky remarks, lusts after women, and that’s about it. In many ways, Jimmy is not very different from the soldiers continuing the wars he claims to be against. Because of his detachment and distance, the horrors of war are little more than background noise (a remark the character himself basically makes when talking about sleeping in the hotel in the green zone, how the blast shields keep out a lot of the noise, but not the mortar blasts and gunfire), unpleasant detours and interruptions, and so on. With the authors and artists choosing to mix brutality with satire, parodying almost everyone in the text, including Burns, it’s difficult to see “Shooting War” as anything but a doomsday scenario played out by vaudevillian actors, none of which I particularly cared about.

It’s difficult for me to think about war reporting without Michael Herr’s Dispatches quickly coming to mind. Seeing as Herr’s account of Vietnam inspired elements of Full Metal Jacket and Apocalypse Now, and that Herr helped write the screenplays for both films, it’s not difficult to see how my fondness for Dispatches played against “Shooting War.” Where Herr’s Dispatches viscerally displays the horrors of war, with the author himself changed by the events he lives through, Jimmy Burns’ emotional register seems rather limited — he sometimes looks scared, looks bored a lot, drinks a bit, shoots off a few snarky remarks, lusts after women, and that’s about it. In many ways, Jimmy is not very different from the soldiers continuing the wars he claims to be against. Because of his detachment and distance, the horrors of war are little more than background noise (a remark the character himself basically makes when talking about sleeping in the hotel in the green zone, how the blast shields keep out a lot of the noise, but not the mortar blasts and gunfire), unpleasant detours and interruptions, and so on. With the authors and artists choosing to mix brutality with satire, parodying almost everyone in the text, including Burns, it’s difficult to see “Shooting War” as anything but a doomsday scenario played out by vaudevillian actors, none of which I particularly cared about.

The medium of the web comic seems to have led to many of the creative decisions behind “Shooting War” — the focal character of a web comic is a blogger, the archetypal detached, snide rabble-rouser or hipster “douchebag.” The fact that we quickly see Jimmy on television screens and on the covers of magazines is interesting, almost as if the creative forces behind the web comic still see older, established manifestations of mass media as “more authoritative.” (It’s also difficult to ignore the constant advertisements for the print publication of “Shooting War,” a text that allegedly offers the narrative a life it couldn’t find online, with “important story & art changes” that I shouldn’t miss.”) The web gives birth to both “Shooting War” and the journalistic career of its focal character, yet the story moved to the “established,” “respected” medium of print, a medium in “Shooting War” that eventually claims Jimmy is impotent, unable to “get it up” in the world of television journalism. A web comic finds an audience and jumps mediums; a blogger stumbles into a journalistic career, but fails to connect with anyone but “sluts” who want to have his baby. What is “Shooting War” trying to tell us about the internet? Is it really just a place to watch porn and bitch about movies, to paraphrase the once-humorous filmmaker Kevin Smith, and not a legitimate medium for the expression of ideas? It’s interesting that the longest web comic we read seems almost ashamed to have started out on the internet.