Response to post by

Josh,

I am familiar with the angry student’s reaction to being blamed for deeply immoral acts in which they did not participate. I don’t think any of my students were initially guilty though, in fact, a feeling of entitlement toward the separation from acts of their ancestors or ethnic group is what I have encountered. I completely agree with your stated dilemma: “Do we have to ignore history and responsibility to move on?” Between political correctness and worries about self-esteem, it’s hard to put an idea out there that doesn’t offend someone and still makes a point. In a much lighter take on a serious subject the Marjane Satrapi book Persepolis, mentions this phenomena in relation to how Iranians are viewed outside of the Middle East.

The protagonist is a bright, outspoken girl who grows up during the Islamic Revolution and the War with Iraq. Her family sends her to Vienna to attend school where she would be safe. Marjane makes two trips back to Iran and always feel like an outsider no matter what culture she is in, Middle Eastern or European. Once Marjane and her mother are ridiculed by their own countrymen in a supermarket for having taken in refugee friends at a time when the food supply in Tehran is sparse. Later, when Marjane is in a French convent, a nun shows contempt for her because she ate pasta out of a pot instead of putting it on a plate first, “It’s true what they say about Iranians, they have no education.

The protagonist is a bright, outspoken girl who grows up during the Islamic Revolution and the War with Iraq. Her family sends her to Vienna to attend school where she would be safe. Marjane makes two trips back to Iran and always feel like an outsider no matter what culture she is in, Middle Eastern or European. Once Marjane and her mother are ridiculed by their own countrymen in a supermarket for having taken in refugee friends at a time when the food supply in Tehran is sparse. Later, when Marjane is in a French convent, a nun shows contempt for her because she ate pasta out of a pot instead of putting it on a plate first, “It’s true what they say about Iranians, they have no education.

Responding, “It’s true what they say about you too. You were all prostitutes before becoming nuns,” gets Marjane thrown out of the boarding house to live on her own, while the Mother Superior writes a letter to her parents that she left voluntarily because she was caught stealing a fruit yogurt.

Marjane’s method of survival is to endanger herself. When she is in Iran, she constantly flaunts Islamic dress codes and behavior norms. Once she tries to commit suicide by drinking vodka, cutting her wrist, and taking pills, and laying in a hot bath. Alone is Vienna, she spends about two months on the streets in the middle of winter, eating out of trash cans and smoking dropped cigarette butts. Imperiling her health, yet, she luckily ending up in the hospital, she tries again to make a go of it in Iran. There she goes to a therapist and takes antidepressants make turn her into a zombie.

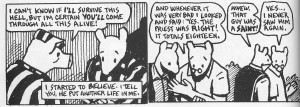

While talking to psychologists she realizes she has tremendous guilt because, as hard as her life was on the street was, it was nothing compared to the political murders and bombings her family was experiencing at home in Iran. She will never forget the terror of being arrested on the street or having her favorite relatives executed. Marjane sustains the collective trauma of the Iranians who lived through that period and the burden of personal family trauma going back several generations to the family of the shah. She, like Spiegelman, uses writing to convey the times as they were, leaving a detailed and generous view into something I can only imagine.

-Deb