I found Shooting War to be a really interesting read on a couple of different levels. Its pointed commentary on contemporary media and U.S. foreign policy doesn’t pull any punches, and makes Wilfred Santiago’s political condemnations from In My Darkest Hour look mild by comparison. I tend to find myself in agreement with much of the criticisms the creators lob at the increasingly irresponsible, corporate media machine, and the neo-con politicians who pushed so adamantly for the war effort. These criticisms, along with the larger themes present in the text obviously make the story very relevant to ongoing discussions on the contemporary convergence of politics, war, corporate America, entertainment, and media. With all of that said, I do feel the work suffers from being too overt in these criticisms.

In general, I think the political and cultural criticisms of the text might have been more effective, or at least easier for the reader to take seriously, if they were presented in a more subtle fashion. In particular, the climactic moment in which the terrorist leader lectures Jimmy in front of a huge screen of George W. Bush was so blunt and obvious in its political message that is seemed more like a Michael Moore documentary than a work of fiction. I don’t want to characterize this moment as creatively lazy, the shock value of the over-the-top violence and true to life political criticisms is certainly intentional on the part of Lappé and Goldman, but a more subtle approach might have ultimately had a stronger resonance for me. I think in most cases, the reading audience is smart enough to get the political message – the creators don’t need to hit us over the head with it.

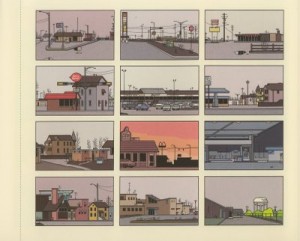

Changing gears here, but from an artistic standpoint, I really enjoyed the use of photographic images to create the background for the many of the full page panels that dominate the text. This technique added to the gritty feel of the text, and strengthened the too-close-to-reality-for-comfort atmosphere.

John