Overall, I wasn’t blown away by Shooting War. However, that is not to say there aren’t parts of it that really got my attention, especially stylistically so. I’m not exactly sure how the authors created the webcomic, but it looks like something straight from Comic Life, the Mac application that comes automatically with most of their newer computers. The way the word bubbles look pasted on top of the art instead of fully integrated into it is what specifically reminds me of this program, and it is this perceived lack of integration between the words and the images that initially put me off from the comic. I thought it looked cheap, and sort of rushed through; however, that’s not to say that the creators didn’t succeed in doing some pretty cool things with what they were working with.

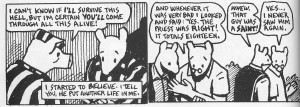

One thing the creators did that I liked can be seen in Chapter 2, scenes 5 and 6, where the interviewer’s word bubbles are literally laid over top of Jimmy’s when she is interrupting him. It’s not a huge thing, but it was a place where I felt the word bubbles were doing more than just sitting on the page narrating the story. I feel like in so many of the scenes the bubbles begin to take over the frames, mostly due to what looks like a lack of space. In other cases, instead of doing bubbles, the narration or dialogue is simply typed on the side of the frame with a black background. At least in Chapter 2/Scene 5 and Chapter 2/Scene 6 the bubbles are given the physical task to represent the actual overlaying of voices (the interruption) in the story’s action. I felt this was one place that the word bubbles were doing more than just sitting on the page taking up space.

Another place where I think the author’s succeeded in doing something interesting with the words was in Chapter 2/Scene 13. Here, in the middle panel, some of the words (“There’s nothing left for you here.”) are actually taken out of a bubble and placed directly in Mr. Newfeld’s eye. The effect is that Mr. Newfeld’s eyes are what is conveying the message to Jimmy that nothing is left for him in New York, or even in America. While the text could logically follow from the bubble immediately before it, and then the bubbles after it could act as further explication of Burns’ situation, I read it as all the bubbles being a continued sentence/thought, and the text in Newfeld’s eye as it’s own message. This is both because of the placement of the text outside a bubble and because I think the look Newfeld is giving Jimmy is supposed to convey a much more direct and to-the-point message than his actual words. Newfeld is a news man and a business man, and as such quite throughoutly long-winded, but here we encounter a place where the man can convey a simply, though depressing, message with just the expression of his eyes.

I’m going to stop with these two examples of interesting things done with the text, but another sort of related cool thing is in Chapter 3/Scene 4, where the rocket actually stretch the length of the scene, across 3 panels. The way it connects the scenes and portrays a sense of time and imminent danger, I though, was really cool.