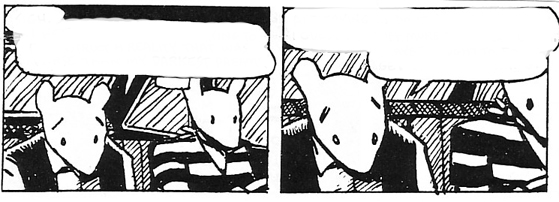

Looking through the final chapter of Maus, I’m struck afresh by how many of the images shown are headshots. I’ve been teaching a bit of visual rhetoric in my English 101 class this past week and we’ve talked there about how these type of perspectives in media emphasize emotions of intimacy, directness, honest conversation…

It’s completely understandable why Spiegelman relies so heavily on this particular angle in the last chapter, and throughout the book. As we read in Brown and discussed at length in our class last week, Maus is primarily an exploration in oral history, in memory and imposed meaning. Of course conversation is going to be emphasized!

But it also strikes me that Maus may rely on the printed word a bit more than the previous graphic novels we’ve read. For example, I think you could probably read The Dark Knight Returns and figure out an awful lot of what was going on—“subtexts” and all—from the visual narrative alone.

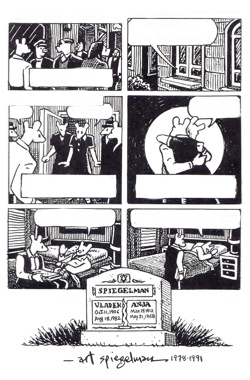

I’m not sure, as of yet, if you could do that with the visuals of Maus. Rather than a sin of illustration omission, however, I suspect that this has to do with the fact that this piece may contain far more subtexts, far more intricacies than any of the other texts we’ve perused so far. For example, how much can you glimpse, let alone unpack, all the intricacies of the last page of Maus (as discussed by our Chute reading of the week) from visuals alone?

Maybe it’s unfair to compare Maus to Miller. And yes, Watchmen and Sandman both had visual narratives that were also purposefully set off against the written narrative. But I can’t help thinking that the written narrative of Maus is quite a bit more complicated and integral than any other text we’ve examined yet.

Maybe it’s the inherent nature of “nonfiction.”

Again, if nothing else, emotions are simply depicted in Spiegelman’s drawings, forcing our in-depth deciphering process to rest chiefly on the written word. Which we have to do; at both a basic and more complicated level, this is a book about relationships, past and present, as that final page of Maus clearly comments on.

Have you tried looking at these books without reading the words? Imagining a page with nothing but pictures (a lá Eric Drooker’s Flood)? What revelations—if any—has that given you?

As a final, somewhat-related note: I had a hard time with Chute’s point making Spiegelman into an overt modern-day political commentator via bodies in the trees near the road, etc…you?

In some ways, and not to disparage either “Maus” as a graphic novel or graphic novels as a powerful medium for emotional and existential exploration, I’ve often thought that “Maus” would have worked as a novel far better than the works we’ve read previously, if only to compare mediums where pictorial elements were important with those that rely entirely on words. This isn’t to place novels on a pedestal or to say that novels are the only mediums for “truly important” stories, but Maus as a piece of oral history, as a piece that relies heavily on the dialogue of the characters, could perhaps have worked, have resonated, as a novel in the hands of another artist, obviously someone whose creative process is facilitated through words alone, unlike Spiegelman whose creative process leads him to words on a page alongside illustrations.

That said — and obviously given my blog post I have some rather strong issues with Chute’s essay — I felt the Chute did a pretty solid job demonstrating to me why “Maus” worked best as a graphic novel, or, to put it another way, would not have worked as well as a novel. Her idea about Vladek packing suitcases and Art artistically packing a panel was pretty well laid out and convincing. Even though the illustrations may not have worked alone, as your post points out in a pretty fine fashion, I’m not sure words alone would have worked either; in any case, words alone would not have led to the place “Maus” inhabits, and that is a pretty damn interesting, fascinating, and wonderful place.

On your closing question, I’m also puzzled to the point Chute was trying to make. I’m not necessarily moved to think of bodies from the Holocaust hanging in trees near the Catskills as a political statement. I’m more moved to think of the hanging bodies as the world in which Vladek is forced to relive as Art is pressing him to recount his life as a Holocaust survivor. If anything, I thought it was to demonstrate the toll Art was asking his father to pay in the name of creating “Maus”; Vladek had to relive, to see again all of the horror he had left behind him.

Lars, awesome points. I agree, I’m glad it’s a graphic novel.

Sidenote: it was the Maus-inspired Persepolis that first got me into graphic novels.

Yeah, I thought Chute seemed to want to read political statements into an awful lot. I also interpreted the bodies in the trees simply as the haunting of memory…

I think Maus works best as a graphic novel simply because of Spiegelman’s training and skill in that medium. I don’t think his prose would have been up to it on its own – achieving such subtle effects as the calendar being interrupted by Franciose – a neat, elegant, humorous yet emotionally fraught moment that I think could only be achieved by a true stylist. And the effect of overlapping time would have been much harder to acheive, if it is possible to achieve it at all in a much more ontologically linear medium such as prose (I’m trying to avoid the Chute-esque idea that linear is “limited’ or “rigid,” since I think that mistakes the true linearity of thought, understanding, and even reading comics itself – but I do think that if there’s a scale of linearity, prose is certainly more wedded to the linear path and requires really exceptional efforts to be non-linear and yet coherent in ways that comics can acheive much more economically).

I thought the bodies were mostly a sort of magic realism, or fantastic layering of the past onto the present through Vladek’s narrative. I’m afraid I didn’t (and still don’t) give them as much thought as Chute does.

I may be missing something regarding Chute’s point about the bodies hanging in the Catskills, but isn’t she simply offering that panel up as another example in which Spiegelman shows the past intruding upon the present?