Kenneth S. Greenburg’s “The Confessions of Nat Turner: Text and Context” may be one of my favorite supplementary texts we’ve read for this class — extremely well versed in the world in which Nat Turner lived and rebelled, and wonderfully fitting Turner, Gray, the rebellion, and the text into the world we now inhabit. While the piece consistently impressed me, one section particularly struck me: the idea that the “indiscriminate slaughter” (Greenburg 20) that filled the first phase of Nat Turner’s rebellion (the latter phases never came to be) “was consistent with the style of warfare Nat Turner must have read about in the Bible” (20; italics mine).

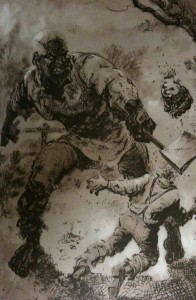

While much is made of Turner’s faith and belief that he was given a “special purpose” (1) in this world by forces from the next in Greenburg’s piece and both Gray’s and Kyle Baker’s Confessions, only Greenburg seems to attribute not only Turner’s “purpose” to Christianity, but his violent methods. Often the Bible is thought of a book of redemption and salvation by Christians, not as a book where one can find some form of justification for “indiscriminate massacre” (20). Perhaps it is as simple as the distance in years between the Bible’s conception and our world today, but I feel it would be difficult to imagine anyone arguing now that images such as can be found on page 135 of Baker’s text should be discussed in any way as having their justification, footing, or roots in religious scripture, yet Greenburg is quick to point out the prophet Ezekiel telling his followers to “Slay utterly old and young, both maids, and little children, and women…” (Greenburg 20) if they are non-believers, thus somewhat linking Baker’s horrific image of a child having his head removed by an axe with a religious narrative — Ezekiel told his followers to slay “those who had broken faith” (20); Turner tells his followers to kill all the whites they encounter as the first step in a religiously ordained “holy crusade” (16-7).

While much is made of Turner’s faith and belief that he was given a “special purpose” (1) in this world by forces from the next in Greenburg’s piece and both Gray’s and Kyle Baker’s Confessions, only Greenburg seems to attribute not only Turner’s “purpose” to Christianity, but his violent methods. Often the Bible is thought of a book of redemption and salvation by Christians, not as a book where one can find some form of justification for “indiscriminate massacre” (20). Perhaps it is as simple as the distance in years between the Bible’s conception and our world today, but I feel it would be difficult to imagine anyone arguing now that images such as can be found on page 135 of Baker’s text should be discussed in any way as having their justification, footing, or roots in religious scripture, yet Greenburg is quick to point out the prophet Ezekiel telling his followers to “Slay utterly old and young, both maids, and little children, and women…” (Greenburg 20) if they are non-believers, thus somewhat linking Baker’s horrific image of a child having his head removed by an axe with a religious narrative — Ezekiel told his followers to slay “those who had broken faith” (20); Turner tells his followers to kill all the whites they encounter as the first step in a religiously ordained “holy crusade” (16-7).

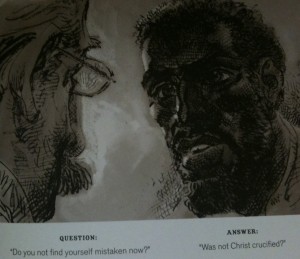

I am sure I am far from the only one who is unsettled by the idea of Nat Turner as a hero (Baker calls Turner “my hero” in his introduction (Baker 7), somewhat coloring the text for me) as well as the central figure of an “indiscriminate massacre,” but I am also rather unsettled by Greenburg’s rather keen observation that Turner garnered his violent plan from the pages of the Bible. Baker directly confronts this issue, depicting Gray asking Turner, “Do you not find yourself mistaken now?”, to which Turner replies, “Was not Christ crucified?” (189). Turner believes that his actions are ordained by God, that his “style of warfare” taken from the Bible is just and righteous, and that his hanging will cement his place as a religious prophet and figure, paralleling himself and his actions to Christ’s own.

In many ways I can understand how the horrors of slavery could drive an enslaved person to violence. What I am having a problem with is the fact that not only is Turner presented as a Christ figure by Baker (a reflection of Turner’s own presentation of himself as a Christ figure, though Gray’s misrepresentation of Turner should also enter this debate), but that in order to accept this portrayal, one must also accept Greenburg’s idea that Turner learned his style of violence — an indiscriminate massacre that targets every white person, not only slaver owners — from the Bible, and that this kind of violence has any place, be it in the pages of scripture or in a southern Virginia town near the North Carolina border as a result of “man’s inhumanity to man.” It is here that I have a difficult time accepting Turner as a “hero” or as a Christ figure for I can’t understand any way, not even through paralleling Turner and his actions alongside those of violent episodes depicted in scripture, that Turner’s actions reflect a true hero or Christ figure, not at least as I have come to understand those terms in today’s world.

As a flawed man, I can understand Nat Turner and his actions; as a hero, as Baker claims early on in his text to conceive Turner as, I cannot — I don’t feel Turner’s actions, even if they are understandable, are in any way heroic.

Great observations. I found Greenberg’s case quite feasible; Turner clearly was influenced by Old Testament literature/myth/story. I think that’s part of the story that so fascinated/excited/repulsed his contemporaries (as would be the case with John Brown some time afterwards).

Not only did Turner represent a “perversion” or at least “abnormality” of intelligence to 19th century thought, he also represented someone who could read the same text and be inspired to quite a different line of thought…again, another subversion. (I do have a hard time reading Baker’s book as an argument for literacy, however, despite the eloquent please of the preface).

For the record, I’m not sure this inspiration is unique or inherent to the Old Testament, however. The Greek myths of old were notorious blood baths (as Gaiman loves to point out). Of course, the majority of Hindu, Muslim, etc. texts are just as plagued by incidents of violence and the justification thereof.

Perhaps what is particularly troubling/unsettling about Turner’s reading of the Old AND New Testament is that he is able to combine the bloody vengeance of the Old with the martyrdom of the New. Needless to say, I share your assessment that his actions fail to “reflect a true hero or Christ figure.”

Reading Turner’s own “Confessions,” there seems to me that he was aware of some of his own conflicted convictions/feelings on the matter. Of course, how much of that is his own voice, and how much it’s that of Gray’s, is a question lost in history…

There’s gotta be a way for me to edit a comment…anyway, make that “pleas” not “please.” Ha!