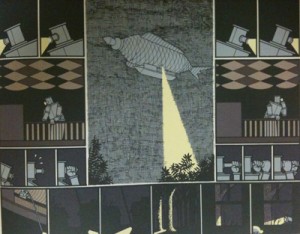

Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth wonderfully plays on the ideas of perspective, objectivity, and subjectivity, as well as the author’s and audience’s distance to the story and its characters (as Bedehoft argues, using the “cut-outs” in the text as examples), to emphasize how one’s experience of passing time is often interrupted and affected by history, memory, and fantasy. In Jimmy Corrigan, these interruptions make up a significant portion of the text, suggesting that Ware sees time not only as the passing of seconds, minutes, hours, and days, but as the moments we daydream staring out the window, thinking back upon our past experiences, worrying about our futures, fantasizing about opportunities that await, wincing at embarrassments from adolescence, dreading horrors lurking in the shadows of an unknowable future, and so on. Time not only passes Jimmy by, but is filtered through him — the minutes can pass slowly and awkwardly, with other characters trying to engage the socially inept Corrigan, or these minutes can seem like hours in which robots watch their younger selves from the deck of airship, only to wake and shed their metal plating (and in this moment between dreaming and waking, being next to a peach tree and under a bird, with peaches and birds being two of the numerous leitmotifs Ware uses throughout Jimmy Corrigan) on an airplane headed towards Michigan to meet an unknown father.

Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth wonderfully plays on the ideas of perspective, objectivity, and subjectivity, as well as the author’s and audience’s distance to the story and its characters (as Bedehoft argues, using the “cut-outs” in the text as examples), to emphasize how one’s experience of passing time is often interrupted and affected by history, memory, and fantasy. In Jimmy Corrigan, these interruptions make up a significant portion of the text, suggesting that Ware sees time not only as the passing of seconds, minutes, hours, and days, but as the moments we daydream staring out the window, thinking back upon our past experiences, worrying about our futures, fantasizing about opportunities that await, wincing at embarrassments from adolescence, dreading horrors lurking in the shadows of an unknowable future, and so on. Time not only passes Jimmy by, but is filtered through him — the minutes can pass slowly and awkwardly, with other characters trying to engage the socially inept Corrigan, or these minutes can seem like hours in which robots watch their younger selves from the deck of airship, only to wake and shed their metal plating (and in this moment between dreaming and waking, being next to a peach tree and under a bird, with peaches and birds being two of the numerous leitmotifs Ware uses throughout Jimmy Corrigan) on an airplane headed towards Michigan to meet an unknown father.

As Bredehoft notes in his essay “Comics Architecture, Multidimensionality, and Time…,” the historian Hayden White “describes one of the central understandings of contemporary historiography as suggesting that ‘events must be not only registered within the chronological framework of their original occurrence but narrated as well, that is to say, revealed as possessing a structure, an order of meaning, that they do not possess as mere sequence” (Bredehoft 886).

The actual narrative of the contemporary Jimmy in Jimmy Corrigan could be easily laid out, revealing a tragic tale of a shy, emotionally stunted man meeting his father for the first time in adult life, laying the first tentative foundations of a relationship with his adopted half-sister, only for his father to die as the result of a car accident and his half-sister literally pushing him away in a moment of suffocating grief. But Ware does not present this story alone — instead, Jimmy, who is almost incapable of expressing/presenting himself (or the ‘order of meaning’ of the passing events that make up his life) in his own words, is expressed/presented through his dreams, daydreams, nightmares, and imaginative currents. In many ways, Jimmy Corrigan‘s narrative and pictorial presentation are indebted to works like Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, where the present is constantly interrupted, diverted, colored by and juxtaposed to past recollections and daydreams. In these works, time is never transcended, but is presented as subjectively malleable — a watched pot never boils, as my mother used to say to me.

The actual narrative of the contemporary Jimmy in Jimmy Corrigan could be easily laid out, revealing a tragic tale of a shy, emotionally stunted man meeting his father for the first time in adult life, laying the first tentative foundations of a relationship with his adopted half-sister, only for his father to die as the result of a car accident and his half-sister literally pushing him away in a moment of suffocating grief. But Ware does not present this story alone — instead, Jimmy, who is almost incapable of expressing/presenting himself (or the ‘order of meaning’ of the passing events that make up his life) in his own words, is expressed/presented through his dreams, daydreams, nightmares, and imaginative currents. In many ways, Jimmy Corrigan‘s narrative and pictorial presentation are indebted to works like Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, where the present is constantly interrupted, diverted, colored by and juxtaposed to past recollections and daydreams. In these works, time is never transcended, but is presented as subjectively malleable — a watched pot never boils, as my mother used to say to me.

Instead of presenting the passing moments of time between when the oven is turned on the water boils within a pot — be it the life of the younger or older Jimmy Corrigan — Ware allows us a glimpse inside of their imaginations, dreams, and nightmares, the interruptions that fill their heads as the water heats up, and demonstrates, as Bredehoft points out in his essay, how time and history unknowingly connects the characters, as when “Jimmy unknowingly looks through a window installed by his own great-grandfather, literally inhabiting a space once filled by his ancestors” (879), or pictorially represented in the history of the torn photograph Jimmy keeps in a drawer — a page which not only seems to condenses time and history, and demonstrates how the past is always entwined in the present, but interestingly links Jimmy’s window frame with a billboard outside, connecting Jimmy’s (lonely) home and existence with that of the city outside, even as it retreats from the wider shot of the city into the deadening emptiness of Jimmy’s home (877).

I think it’s important that you mention the “author’s and audience’s distance to the story and its characters” here. You don’t mention this because you take your post in a different direction, but I was very impressed by the way Ware handles distance on the actual pages of the text. We so often see scenes where a home or restaurant is viewed from a number of perspectives on the same page. There’s the opening pages where we see a distand galaxy, then a world, then it zooms ever closer. Similarly, one of the restaurant scenes shows us father and son sitting at a table inside the restaurant, then we view them through a window, before retreating to the back of the parking lot where we only see two lonely figures sitting in the lonely restaurant’s window.

I felt these movie-like depictions of of setting helped reinforce the ideas you talk about in this post. By playing with settings in this way, Ware helps reinforce Jimmy’s positions as a lonely person. Jimmy can be up close and personal in one frame, but Ware reminds us of his positions as an awkward loner by pulling the lens away and showing us just how distant he really can is.

I had meant to go more in depth about distance, but sort of forgot… Yeah.

In some ways the Distance theme could easily be a post in itself, especially when you have authorial distance, the blurring of narrator and author, the engagement of the audience and the times the reader cannot connect with Jimmy, and so on.

Guess it’s good I didn’t get on to this as my post would have become unbearably long.