“Reading” Gaiman, it is sometimes difficult to say whether it is Gaiman himself that has the majority of the appeal, or if he should share top billing with his illustrator(s). The difficulty of separating the writer from the illustrator, or whether we should try to separate them at all, is one of the compelling questions of reading graphic novels.

Read “Coraline” and there is no doubt of Gaiman’s power to drive a narrative without the benefits of illustration (although there are illustrations on the cover and front piece and at the beginning of each chapter; 7 in all). When I read the script for Calliope for the first time, without turning back to look at the finished version, I was trying to picture the action, using only his description and blocking out what I remembered. It read like a script for a stage play or a movie, where the reader has the leeway of their imagination. I found myself wishing I had read the script for Calliope before reading the graphic treatment. Is the story affected by taking away our ability to use our own “graphics?” Is there enough of a story there to stand alone and be substantive?

Reading the script the second time as I flipped back and for between the two, I found a number of instances where the illustrators didn’t follow Gaiman’s script. The script of page 9, for example, seems to be completely disregarded except for the dialog. The panel layout, the shots of Calliope and the descriptions of the muses doesn’t fit what Gaiman asked for. Because it is labeled as the “Original Script of Calliope” there is probably a revised version that is more of a collaboration with the illustrators. There are a number of other scenes as well. I wonder how the story would have “read” if the script was followed exactly?

I think part of Gaiman’s ability to create such successful novels is in selecting the illustrator. “Midsummer Night’s Dream,” the only story we’ve read where he collaborates with Charles Vess, is a good example. Vess captures the bucolic, “Prince Valiant” quality of England that I have come to associate with contemporary illustrations of that period. They establish a mood that fits the story line, even the night scenes, where a more “gothic” vision of Sandman is portrayed.

Gaiman gets top billing for the Sandman series and he should. He created the character and ideas, but he needs his collaborators to bring the fullness of his vision to the page.

Sandman Takes a Back Seat

I find “Sandman” to be very intriguing and I enjoy many of the stories presented. I’m fairly indifferent to the Sandman/Dream/Morpheus himself, however. In trying to think about what to post on I thought about the many great stories, disturbing scenes (touched on in other posts), fascinating characters, etc., and I suddenly realized that none of what I was thinking about dealt with Morpheus himself.

So of course this got me thinking about why I wasn’t thinking about Morpheus, even though it is his comic book. But is it his book? Looking at pretty much any of the issues contained in the two volumes we read one finds that Morpheus is almost a side character. Even in the first volume “Preludes & Nocturnes”, the overall arc of which seems to be about his imprisonment, escape, and his quest to regain his “tools” and reclaim his kingdom, Morpheus is hardly there. It seems like none of these episodes are his story, but belong to other people, like John Constantine, Dr. Dee, Richard Madoc, Caliope, the Cats, Death, and so on. Dream always plays some role (either remembered or active) but he really is not the focus of the series.

I think this is entirely intentional. Have you ever tried describing a dream to someone, only to realize halfway through the story that you cannot explain it properly and that the poor listener does not want to hear about how they were in your dream, but they weren’t themselves, but they were, but it wasn’t like something? Dreams do not work the same way as reality, and dream stories do not work like regular stories. Dreams are part of the effluvium; you are aware of them, but they are not real and they dissipate upon waking.

Morpheus is dream incarnate. He is not just the king of dreams; he is dreams. As such, he is part of the effluvium at the outskirts of consciousness. How could he be the focus of a story? Instead, he is a vessel. His comic book is a vessel for these other stories to be told. He plays a part, in that his existence means the stories can exist, but he is not the story.

Nature of dreams in Sandman?

As ruler of the dream world, Morpheus may not be viewed as a totally benevolent character, but in most instances in Volumes 1 and 3, it seems like his motives are generally geared towards doing the “right thing” (punishing his captors, giving Rachel a humane death, stopping Dee, freeing Calliope). Yet while readers can see Morpheus in a mostly positive light, the act of dreaming in and of itself is given a much more ambiguous moral treatment by Gaiman. This sense of moral ambiguity in the text seems to grow even stronger if we are meant to read dreams as a reflection of society.

In Volume 1, dreams are shown to be volatile and extremely destructive forces. We see the devastation on an individual scale with Rachel. Her addiction to dreaming destroys her physically and mentally, also leading to the death of her father (although I guess there’s something still alive in the dream-inducing goo?). Morpheus and Constantine finding the Creeper being “eaten alive” by his dreams reinforces the negative implications of dreaming. On a larger scale, when Dee unleashes the power of Morpheus’ ruby, the darker side of human dreams gives release to the “blackness from their souls” (pg. 188), overtly referencing the nastier parts of our human nature.

“A Dream of a Thousand Cats” was the only tale in Volume 3 in which dreaming plays a central role, and it presents dreams in a vastly different light than Volume 1. This story was my favorite in either volume – partially because dreams are shown to have a dual role for the cats as both the reason for their oppression at the hands of humans, and as beacons of hope for a better future. Certainly this episode has its darker elements as well, but Gaiman tells a more playful, somewhat optimistic story about the nature of dreaming here. But maybe this optimism rests in the fact that readers are witness to the dreams of a cat, and not a human.

The texts lead to some interesting questions about dreams, and also about what the nature of our dreams say about us. Does Gaiman use dreams as a framework to make his own moral commentary on society/human nature? Or do dreams serve predominately as the canvas for him to tell his stories involving anthropomorphic, biblical, mythological, and historical characters? I would imagine it’s a little bit of both, but I wonder if those who’ve read a larger sample size of Sandman have any other insights into the nature of dreams in the texts?

John

Masks and Disembodied Faces in Sandman Vol. 3

While reading Sandman Vol. 3 I found a repetition of masks and/or disembodied faces, which basically are masks. These faces haunted me a little bit, and I noticed that in the artwork at least, perhaps accidentally, they are present in each and every story. More than that, they seem to have a sort of power, or at the least denote power, sometimes too much power as in Facade.

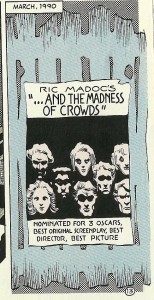

In “Calliope” the faces are on page 23, panel 6:

These faces seem to represent the power that Ric Madoc has because of his new-found muse. As the poster shows, Ric’s creativity has earned him nominations for 3 Oscars, best original screenplay, etc. Beyond that, however, Ric’s true self was unable to create a second novel and so he uses his muse to become a successful novelist. In other words, he uses the mask that he brutally forces from Calliope to pretend that he has talent. The mask, then, gives him power.

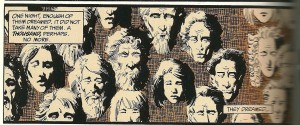

We see disembodied faces again on “A Dream of a Thousand Cats” on page 54, panel 2:

In this case these are the faces of the people who dreamed a world where humans were larger than cats. These are the faces potentially responsible for the current power humans have over the feline species. It could be said that these are the faces that created the current mask of reality, and I couldn’t help but see a connection because of the disembodied aspect of them, similar to the poster in “Calliope.”

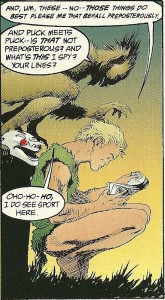

“Midsummer Night’s Dream” is full of masks, but perhaps the most telling panel seems to be on page 77, panel 2:

Here we see the true Puck looking down on the human who is looking down on the Puck mask. In terms of the story, the masks are the reason the faeries and goblins came to Earth again. The humans are pretending to be the creatures that they are performing for, and in so doing have power in the instance of the play. While the hobgoblins and others want to eat the humans, or hurt them in some way, they are unable to while the masks are on. It is only after the human-Puck takes off the Puck mask that the true Puck can kill him.

Finally we come to “Facade”, where page 90, panel 2 seems to be the best representation of the masks Rainie has used:

These masks are both show Rainie’s power in that she can create them in the first place, but they also show her weakness, in her inability to throw them away. She wishes she could keep the masks on forever, but unable to do this she instead gives a little part of herself to each and every mask she creates. In this case it seems that the sacrifice she unwillingly made for the power she currently has is one she is unable to accept. She is completely alone in a room full of masks that unceasingly stare at her.

Throughout these short stories masks play an important role in showing the cost of power and perhaps also the flimsiness of reality.

Gaiman’s Script and Dr. Destiny Balloons

I thought the most rewarding part of reading these two volumes of Sandman was the fact that we got a script of Gaiman’s at the end of volume 3, for “Calliope” which is actually the particular story that I found the most intriguing of that volume. After reading the Comic Book Creators chapter for this week’s reading, I found myself even more interested in the process of collaboration that occurs between the writer and the artist(s). In Gaiman’s example, I found it refreshing that even though he had a full, formal-ish, script for the comic, there was still obviously room for the artistic input of Kelley Jones.

The structure of Gaiman’s script is fairly formal, in my opinion. He gives a panel by panel summary of what he expects to happen. When I had read up on collaborations, I thought the idea of a full script would be stifling for the artist, but as Gaiman’s script shows, his tone and execution of the script can be informal, while his expectations for the panel can still be fairly detailed. I think that has to be one of the most effective ways for a comic marriage to work between the creator and the illustrator, when these two are separate entities.

I also found the sequence of collaboration to be a telling element about how the story can come together. When you read the script, the explanation of the panels reads in the present tense, followed by the actual dialogue of the comic. Then, in red we see Gaiman’s notes on how Kelley took the script and penciled it. Yet, seemingly before the images are actually drawn, we also have Kelley’s notes on how the images should be handled when they actually are drawn. My understanding then of how the script becomes the comic would be that Gaiman writes the script, gives it to Kelley who writes notes about how the images should be accomplished, and then we have Gaiman’s notes about the process and how it is carried out by Kelley and then Malcolm who inked the artwork in. An example of this can be found on page ten of the script where we have the text of the script and Gaiman’s comments on the comic process for how Calliope is drawn when we are first introduced to her.

All in all, I found the script to be illuminating. I could see Gaiman’s appeal in the way he can make the script portray a visual that the artist can then execute, while also letting the artist have license with the work as long as the overall point of the panel is displayed.

As a smaller unrelated side post, I found myself liking Dr. Destiny from the first volume, which worries me some, honestly. Yes, he’s crazy and the things he makes the people do in the diner are haunting enough to stay in your mind long after you read/see the pages, but I still enjoyed him because he was memorable, problematic, and well…crazy.

I’ve come to terms with Gaiman’s Dr. Destiny though an analogy. It’s like he’s a balloon (a red one if I had to guess). Sure he makes kids run after him into oncoming traffic and he’ll pop in your hands causing you to lose both your eyes (Freud reference), but at the end of the day and at the ends of the deaths, Dr. Destiny is still a balloon, and he needs to be put back with all those other crazy balloons that could and would wreak havoc on humanity if set free.

Is Watchmen the Right Choice for All Readers?

It’s not surprising that Watchmen was a Hugo Award recipient for excellence in science fiction in 1988. The artwork is purposeful and the storyline is provocative-definitely an alluring mix for young adults and adult readers. Moore’s work is one to return to again and again, with Gibbons’ bright artwork offering readers subtle details and symbolism in each panel and on each page. Readers can relate to the various characters’ struggles to deal with personal weaknesses while appropriately managing their talents or abilities, though a less mature audience may find the story challenging to take- in due to the gritty episodes, contemporary and mature themes and confusing reference to time throughout.

This story is particularly popular because it is based on fictional events (politics, power, war) with interesting characters that are generally complicated with multi-layered personalities. This might be a useful (though unusual!) piece for individuals looking to understand governmental authority and policy and its ramifications for citizens. It examines champions from the past and poses the question of how one might become a hero and the challenges of being widely known by everyone.

As a future librarian I would enthusiastically recommend this graphic novel, especially to patrons looking for a story about a hero, forgiveness and survival. Similar to The Dark Knight Returns, this story offers a more sinister impression of the world while keeping readers mesmerized with quality writing and pace.

The attention to artistic renderings and prose is exquisite; making this a piece that will surely stand the test of time. When asked about his role in creating such a masterpiece, artist Dave Gibbons accurately commented, “…comics are stories in words and pictures.” (http://www. wired.com/ underwire /2008/12/ archaeologizing/); those who enjoy variation in their reading will enjoy this classic, thought-provoking selection.

Superheros as Nazis? Also in this issue: Laurie and Bechdel

No Rules to Break

an·ti·he·ro

–noun, plural -roes.

a protagonist who lacks the attributes that make a heroic figure, as nobility of mind and spirit, a life or attitude marked by action or purpose, and the like.

Would you consider it irony that a super-hero is also an antihero?

The reader is brought into the world of Watchmen by an unreliable narrator, Rorschach. His inner voice filled with criticisms, misgivings and blatant paranoia. From the cops we are told that his body count is impressive and somewhat indiscriminant. This is now a world where vigilantism, or being a masked superhero, is outlawed. There is no place for him in this new world order but retiring was never an option for him.

What about him do we find gripping? Why does a part of us still believe his mental meanderings?

With the Comedian’s death we watch him systematically follow leads that, for the most part, hold loose logic. He immediately leaps to the conclusion that the Comedian’s death is just the beginning of an all out slaughter on heroes. Even though there is no direct evidence to correlate his hypothesis, added to the fact that we know the Comedian had plenty of enemies, we still think there is truth in what he says.

I just find it mystifying that I hold some type of faith in this unreliable character. Am I somewhat programmed to believe in him just because he allied himself on the side of “right”? Unlike Batman, whose moral code is sparse but unbendable, Rorschach only sees himself as judge and executioner. What are a few broken bones if he can get some answers? If he couldn’t get any answers, well, then it’s just a few broken bones.

Maybe it’s his chaotic lawlessness that attracts me, a character that can’t be typified as a criminal or a hero. Someone directly outside the lines of comfortable labeling. The perfect antihero.

All on Faith??? by Travis Rainey

In one of the best novel introductory quotes of all time (in my opinion at least) Alan Moore places before the reader, almost all of the great themes of the Watchmen. Great disclosure of Rorschach’s mind informs us of the state of the union, no, the world. Most importantly, we learn more about the stories characters, masked or of the masses, in these two sentences: “The accumulated filth of all their sex and murder will foam up about their waists and all the whores and politicians will look up and shout ‘save us!’…and I’ll look down and whisper ‘no.” Rorschach assumes he (or the superheroes) is the subject to which the masses are calling. I don’t believe anyone can state that his assumption is unsubstantiated, however, it raises the question, “Where is religion and faith in the masses”?

Also alarming, is Rorschach’s response, although his actions leave questions to any truth behind his words. A world surrounded in choice (as we all have the choice for good and evil), I found it most amazing that even the most powerful of characters, when provided the opportunity to stop the actions of evil, chose inaction. The inaction or wrong actions of so many characters, primarily the masses, whose “filthy” actions allowed America to slip into such a “gutter” have got to be the greatest crime. Can’t blame Veidt. Can’t hate the Comedian. Forget about Rorschach. To me, the masses culminated to the greatest character, interestingly personified by Seymour at the conclusion. I wonder if he has religion…

Mr. Hollis Mason, in his excerpts from “Under the Hood” often spoke of “the moral instruction”; he states he received it from his grandfather and that it was a leading foundation to become the Nite Owl. However, I must wonder, where did this “moral instruction” come from? Alan Moore created a world full of real, down-to-earth, societal and sociological issues but how did he forget religion? Religion, the subject of so may wars (probably the most), discords, battles, skirmishes, debates, and pure disagreements; I find it hard to believe that Alan simply “forgot” the theology of the world. No…no; it was intentional.

First, I suppose religion may have provided an easy “out” for quite a few of the social problems. In a simple line from Dan to Laurie (for I believe she needed the most psychological assistance), “Why don’t we go to church and pray on it.” Of course, there are no guarantees religion could provide assistance, moreover, we have to assume Alan would have used religion to further disrupt the masses although I like to think (and I feel others may too) religion often consoles humanity especially in the face of fears and pain we cannot fully understand or bear. In thought, the purely chaotic world is one of infinite religion, or none at all. I believe this world was the goal; a world full of “The American Dream” where greed, money, and worldly desires are the substantiated goals and religion free falls to the sidewalk.

What are Superheroes for?

As I read Watchmen, I kept trying to figure out who the heroes were. It was, after all, originally a comic book, so didn’t it have to present a morally enhancing solution or lesson to the thematic dilemma? The more I read, the more apparent the paradox became: Did the crowed frames reflect intense involvement or overuse of plot? Was there loneliness or just isolation?

Then the answer came from the source itself, in Elizabeth Rosen’s article on “Nostalgia.” In it Alan Moore considered the effect of violence on the genre and concluded “‘Look, you know, get over Watchmen, get over the 1980’s.’ It doesn’t have to be depressing, miserable grimness from now until the end of time. It was only a bloody comic. It wasn’t a jail sentence.”

So why do we take the Cold War/exploding alien invader story to heart? Well, “Superheroes are still an excellent vehicle for the Imagination…” (Moore). And, while implausible, the multilayered personalities of the Minutemen, Crimebusters, and friends, do present as a modern-day pseudo/psycho drama as warped as today’s headlines and crime shows.

Except for the easy going Hollis Mason and Dan Dreiberg, Nite Owls #1 and #2, these characters are conflicted as a result of their childhoods and the experiences in the terrifying, bloody streets of American in 1985. Here Rorschach play right into the Social Services Department in any big city. Through choice, but mainly chance, come into the system as children and remain in it, maybe forever, from welfare to rehab, and eventually to the criminal justice system. Abused as a child, Walter Kovacs careens from a 10-year old who bites another child in the face to an uncompromising vigilante.

Maintaining the blade-sharp insight, but turning from the position of victim to avenger, Rorschach commits some of the most horrendous scenes in the novel as he is fighting against crime. He and the Comedian became notorious examples of why 1977 Keene Act had to be passed in order to preserve the rights of the yet unconvicted. The shifting mask on his face is ironic as Rorschach is inflexible and while he knows submitting his journal will finish humanity’s faith in himself, he does it anyway and meets his own gory end. Really? Would you tell?

Can Ends Justify Means?

I have read Watchmen several times now and there is something unsettling about it. I think many of us have felt this, judging by the Twitter feed, though we are all struggling to put our finger on it. I think it is because for a book entirely about superheroes, there does not appear to be a single hero among the characters.

Rorschach is often pointed to as people’s favorite character, or the most interesting, and I think there is an initial reaction to think of him as the hero since he is the only one to continue to stand against Veidt. Also, the story begins with his voice and the book also ends with his diary potentially being what will undo the conspiracy. He is n0t the hero, however. While he appears to have many of the traits of the classic American antihero, like a Batman or a Mike Hammer (hard men making hard choices for justice), Moore clearly does not endorse his right-wing, near-fascist vision. As Rosen points out, “the creators of Watchmen make it clear that they also intend to undermine Rorschach and what he embodies.”

Rorschach’s black and white view of morality is not what Moore wants taken away from this story. The whole story culminates in moral ambiguity. I think that is what so many people struggle with. Veidt appears to fill the traditional role of the villain as he kills millions, but he is as close as Watchmen gets to a “hero” because his actions actually save the world. Obviously Moore and Gibbons are deconstructing what it means to “save the world” and playing with the expectations of the reader, Veidt spares the world from nuclear destruction and war by sacrificing millions of lives. Though the other masked adventurers do not necessarily agree that it was right, they can’t disagree with Veidt’s logic and success, with the exception of Rorschach who must also be sacrificed for the “greater good.”

The question comes down to moral relativity versus moral absolutism. Veidt’s moral relativity seems to be answer Moore and Gibbons want us to accept. In the world of Watchmen, there are no moral certainties. The black and white worldview of Rorschach leaves no room for humanity: wrong is wrong, and bad people are always bad. But even the grey, subjective morality of Veidt is not fixed and absolute. As Manhattan points out, “Nothing ever ends.” Veidt’s actions, the conspiracy and the world peace it achieves is only morally correct as long as no one finds out the truth. As long as the lie is maintained, it is the “right” thing, but if the truth is ever discovered, it is just mass murder.

Frame Changes in Watchmen

In his chapter on gutters, McCloud lists the six types of frame shifts: moment-to-moment, action-to-action, subject-to-subject, scene-to-scene, aspect-to-aspect, and non-sequitur.

He then charts them out, showing that by far the most popular in Western comics are the action, subject and scene shifts.

While reading Watchmen I noticed some interesting ways that Moore and Gibbons use frames to create moods and tell the story. I noticed a lot of scene-to-scene cuts, something McCloud says doesn’t get used as much in the West. The thing I found especially interesting about Moore’s use of scene-to-scene framing (I will use specific examples from Chapter 3) is that Moore and Gibbons use scene-to-scene while also employing action-to-action and subject-to-subject in an interesting juxtaposition of images, words and ideas that provides an end result that hits the definition of the extremely rare (in the West) aspect-to-aspect framing McCloud describes.

This blurring creates an interesting effect on both the storytelling and early mood of the novel.

First I would like to dwell a bit on the difference between scene-to-scene and aspect-to-aspect, because I found myself confusing the two at times. McCloud writes that “deductive reasoning is often required in reading comics such as in these scene-to-scene transitions, which transport us across significant distances of time and space” (71). He differentiates these cuts from aspect cuts by defining the latter as transitions that “[bypass] time for the most part and sets a wandering eye on different aspects of a place, idea or mood” (72).

In looking at Chapter 3, especially pages 9–15, when the panels juxtapose Dr. Manhattan’s TV appearance with Daniel and Laurie’s adventure in his apartment and on the streets, I feel like we are seeing pretty clear scene-to-scene transitions since time is a relevant factor. However, the effect of this juxtaposition actually seems to help create the different aspects of a place, idea and mood as outlined in the aspect-to-aspect definition. So let’s take a closer look at this section.

What the scene-t0-scene transitions do so well in this section is create a certain mood: one that shows the current attitude towards masked adventurers, their nostalgia, and the complexity their modern lives pose. Moore really drives this home with the juxtaposed images of Doc Manhattan and Daniel and Laurie that feature one thread of narration–the one that sticks with Manhattan in the TV studio even as the image changes. For example, the TV host says “…And believe me, we have something really special for you tonight” while Daniel and Laurie find themselves surrounded by thugs in an alleyway (12). Later on the same page, the TV host asks “will you be prepared to enter hostilities” to Doc, but the dialogue appears over Daniel and Laurie as they prepare to fight their way out of a bad situation, like they used to in the old days. Moving to page 14, we see much of the same effect. The TV host has just accused Doc of causing cancer in the people he loves, and much of this dialogue is displayed on Daniel and Laurie’s images: “I’m starting to make you feel uncomfortable” as they begin pummeling the thugs; “because from where I’m standing, it’s starting to look conclusive,” as the fight ends; and finally “but the show’s over,” says a an agent as Daniel and Laurie stand, hurt but victorious in the alleyway.

Here Moore uses juxtaposed images to convey a certain sense of the Watchmen’s place in society. Doctor Manhattan is attacked on TV just as Daniel and Laurie are attacked in the alley. Both are under attack at the same time, just in different places and in different ways. The lines of dialogue “it’s starting to look conclusive” and “but the show’s over” help reveal that the Watchmen’s show is over, even if Daniel and Laurie seem to have danced with their nostalgic past in the alleyway. Daniel and Laurie protect themselves in the streets, but their true days of donning costumes and fighting crimes, we are reminded, are long over. Doc Manhattan, the only still-active adventurer, is so hurt by the attacks that he will leave Earth, helping set the rest of the novel’s events into motion and showing that even America’s god-like protector doesn’t receive positive or warm treatment in society; a truly dark time for heroes.

This section also allows us to get a glimpse of the society the Watchmen live in. Media is as vicious as ever, attacking Doc Manhattan by surprise, blindsiding him with news he hadn’t even heard yet to sell papers and increase viewership. The streets are no safer than when the Watchmen “protected” them, as we see a group of armed thugs attack two citizens–who happened to be two of the wrong people to attack.

These juxtaposed frames essentially tell the same story of a world with no room and no trust for heroes, even if the world is still far from a safe place. Moore and Gibbons use scene-t0-scene transitions here to transport us across space and then back again over and over to drive the point home that nobody is safe. The times are dark. The mood is dark. And our heroes are physically and emotionally attacked despite their wishes (at least in the case of Doc, Laurie and Daniel) to be left alone to work (Doc) or live quiet lives (Daniel and Laurie)

What’s interesting is if we were to take away these juxtapositions, for example by stringing just the Doc Manhattan frames together, we’d see a lot of action-to-action and subject-to-subject cuts, as they still exist within the chapter, they just get broken up by the juxtaposition of Daniel and Laurie. By adding in the scene-t0-scene transitions, Moore can double down on his words, using one narrative thread to tell two stories and incorporating action, subject and the obvious scene cuts. This lets us know that the stakes lie on more than just one hero in this novel, and that the stakes are very real and far-reaching. In so doing, he also creates a strong sense of place, mood and important ideas that are more generally tied to aspect-to-aspect cuts.

And he does this all in six pages of switch-off imagery. If that’s not careful, attentive writing, I don’t know what is.

So I bring it to you now: Is this the type of effect that can only really be achieved by comics, allowing for a juxtaposition of images with one written narrative thread that links them? What other types of cuts come into play in this, and other chapters, and offer us similarly deep results? Am I way off base here and did you see something else?

Tales of the Watchmen

Who is the narrator of the Black Freighter? In many ways, he is a mirror of Dreiberg and Rorschack. Like Dreiberg he is naive and harmless, except to those who would do wrong. He is cast adrift in his story as is Dreiberg in his. While both struggle and appear to make a difference, their actions are futile against a much bigger world. Neither seems to control their fate. And, like Dreiberg, he is in love, but his love drives him forward and ultimate causes him to be cast out of society. Dreiberg’s love for Laurie, on the other hand, seems to final give him a place of sorts in the world that remains.

Like Rorschach, the narrator can commit murder when it justifies what he sees as ultimately good. He disguises himself, after murdering the money lender and the “pirate’s whore”, then becomes the “implement of God’s retribution.” (Chpt. 10, page 22) He, like Rorschach, suffers for his inability to see the futility of continued struggle. Rorschach cannot let go of a wrong, even when to expose it would cause catastrophe. Both pay with their lives.

The narrator and Adrian are also alike. While the narrator built his raft on the corpses of his dead shipmates in order to warn the world of the Black Freighter, Veidt confesses that he has “struggled across the backs of innocents to save humanity.” (Chpt. 11, p. 27)

Following the emergence of the narrator as a character in Tales of the Black Freighter, Moore’s comic within a comic, is a gloomy process. A sense of despair, horror and doom dominate the tale and parallels some of the story line of Watchmen. In the end, like Dreiberg, Rorschack, and Veidt, the narrator has no choice. He is destined to ride the Black Freighter, a member of it crew we presume, forever. Their destiny, like the narrator’s, appears to be ordained by forces they cannot control.

It is interesting that Shea, the writer of the text of Tales of the Black Freighter, is also one of the creators of Adrien’s “new life form” (Chpt.11, p. 25) that brings peace to the world by threatening it with extinction. The issues of Tales that Shea writes are published two years after he disappears, with the end coming as Veidt’s plan is realized.

Metaphysical questions

I have a confession to make.

I hate time travel.

It just doesn’t work. Pretty much every story I’ve ever encountered that’s involved time travel is inevitably derailed by the paradoxes of relying on said plot device. From old Star Trek episodes to Lost, from Terminator to The Lake House, my disdain for the convention has only grown. Each plot devolves into a repetitive loop of causality that simply, aggravatingly doesn’t make sense. It’s true that 12 Monkeys—and its infinitely better predecessor, La Jetée—plays with this very idea, but the sight of Bruce Willis screwing up his own life for eternity was every bit as shallow (if beautifully designed) as it would later be in his Disneyfied attempt to redeem it in The Kid.

It just doesn’t work. Pretty much every story I’ve ever encountered that’s involved time travel is inevitably derailed by the paradoxes of relying on said plot device. From old Star Trek episodes to Lost, from Terminator to The Lake House, my disdain for the convention has only grown. Each plot devolves into a repetitive loop of causality that simply, aggravatingly doesn’t make sense. It’s true that 12 Monkeys—and its infinitely better predecessor, La Jetée—plays with this very idea, but the sight of Bruce Willis screwing up his own life for eternity was every bit as shallow (if beautifully designed) as it would later be in his Disneyfied attempt to redeem it in The Kid.

As a pure sidenote: I do confess a hypocritical appreciation for the sheer campy-ness of Back to the Future. It’s so ridiculous that I can overlook all of the improbabilities and accept it for the farcical comedy that it is.

But in general, it wasn’t until I encountered Joe Haldeman’s forward-only time travel in The Forever War that I was able to read a time-travel book without wanting to inwardly throw up at least a little.

I digress. All of this preamble is just merely to say that I found Dr. Manhattan’s existing outside of time to be rather distracting. Make that very distracting. I still can’t decide if I thought it was a well-handled discussion or not. It certainly seems to be a pretty major plot point…

I shared quite a bit of Laurie’s angst over Jon’s “predestination trip.” Can anyone ever explain that kind of thing? Maybe it’s because it’s just an infinite—“godlike?”—idea that my finite brain can’t comprehend. Well, damn it, despite his proclivity for the magic ‘shrooms, Moore’s brain is just as finite as mine, and I’m just not convinced that his character’s monotone “There is no future. There is no past.” schtick is that insightful (if at all).

True, are Jon’s pretentious metaphysical soundbytes even a serious story point? By the end of the story, as he fails to “save the day,” I can see why Moore would want to play with diluting the power of a too-perfect, too-omniscient hero—an ultimately fatalistic subversion that goes more than a step further than the grit of Miller’s Dark Knight. Indeed, the bitter deconstruction of all of society’s ideals is the real, persistent discussion drummed into our heads throughout Watchmen—and it’s a bleak one. Which I guess Jon’s soundbytes do reinforce…

True, are Jon’s pretentious metaphysical soundbytes even a serious story point? By the end of the story, as he fails to “save the day,” I can see why Moore would want to play with diluting the power of a too-perfect, too-omniscient hero—an ultimately fatalistic subversion that goes more than a step further than the grit of Miller’s Dark Knight. Indeed, the bitter deconstruction of all of society’s ideals is the real, persistent discussion drummed into our heads throughout Watchmen—and it’s a bleak one. Which I guess Jon’s soundbytes do reinforce…

Still, in the end, I found Jon’s insistence that “we’re all puppets, Laurie. I’m just a puppet who can see the strings” more than just an emotional downer. How many strings can he see? How does one exist both within and outside of a timeline simultaneously? Why can’t he do more to “fix things?” Is the eternal energy of the universe dictating his life (and in turn, everyone else’s)?

It seems to me that there are two kinds of mysteries in stories–ones that make you bend even closer to the page in wonder and appreciation, and ones that make you sit back and scratch your head in frustration.

Which direction did you lean?

Family Dysfunctions and Lack of Connections

While Watchmen can never be accused of painting an optimistic picture of humanity, one thing that kept coming back to me during this reading was just how flawed virtually every type of human relationship is shown to be throughout the text.

Moore is absolutely unrelenting in his portrayal of marital and parental relations. Rorschach’s childhood is a nightmare of physical and verbal abuse, and Laurie’s strained relationship with her mother leads to resentment and a life of half-truths. Likewise, the vast majority of marital-type relationships in the text are shown to be deeply flawed (Jon and Laurie, Jon and Janey Slater, Sally Jupiter and Larry, Dr. Long and his wife, Joey and her girlfriend). These dysfunctional portrayals of family life fit well with Rosen’s reading of Watchmen as a very blunt critique on nostalgia, and it seems Moore is intent to hit his readers over the head with the message that family lives don’t always live up to the idealized views that society can present.

But Moore also seems to be making an interesting critique on humanity and the general inability in contemporary society for people to form connections with one another. As the true “superhero” of the text, Dr. Manhattan struggles between the roles of protector and threat because of his inability to connect with humanity. Likewise, two superpower nations are on the verge of nuclear annihilation, without seemingly any sense of their shared humanity. Rorschach’s sense of isolation is so extreme that he chooses to lead a life as a deranged recluse. And the physical failure to connect with another person is present on a sexual level in Dreiberg’s impotence.

While much of these failures of connection are righted by the end of the story, it’s also interesting to look at just how these resolutions are brought about. The fate of humanity is saved (at least temporarily) as Americans and Soviets can come together to fight a perceived common threat, but only after millions die. And Dreiberg consummates his relationship with Laurie, but only after putting on his mask and costume.

Moore is certainly making some heavy political statements in Watchmen. But I also think he’s intentionally making some interesting human statements. His goal doesn’t seem limited to simply subverting any idealized views of our relationships with one another. He also seems to be focused in questioning the fabric that serves as the basis for these relationships to begin with.

John

Rant on Character Flaws in Watchmen

Watchmen tells its story amazingly well, but it’s not an enjoyable one. It may be that I want a hero, I want someone who I can like, and Moore makes that impossible. While I’m sure there’s a reason for this, in the end I like likable characters and some part of me believes that these characters and their flaws are somehow wrong.

To start with, Doctor Manhattan certainly offers an interesting character arc in his simultaneous increase in emotional distance from humanity, and his ultimate understanding that humanity is worth saving. But his ease of accepting Veidt’s atrocity renders his new-found love for humans worthless. How could someone who can see atoms so quickly accept that the only way to save humanity is by deceiving them into thinking an alien entered their universe and killed millions?

Veidt is too easy to hate – his money, his egotism, his final plot. And why did he have to kill his servants? Couldn’t he have just kept them on in his frozen palace until they died naturally?

Laurie drives me crazy. She’s useless, except as a girlfriend, and she’s not even good at that. She’s a kept woman by Dr. Manhattan and then runs off to Nite Owl and makes out with him the same night she leaves Dr. Manhattan. Really? She’s a sex symbol who occasionally fights, but only when there’s a man at her side. She doesn’t want to go along with Nite Owl’s new-found heroic desires, but does anyway and we never really know why. My thought is that she can’t function without a man and needs to follow one around in order to even exist in the Graphic Novel at all. She gets her happily ever after, which I suppose is perfect since that’s all she was ever after – the American Dream, complete with husband and a hint that little ones might be on the way.

Nite Owl is a little easier to like as he gains his confidence back through his heroic acts, but he’s really a push-over who only sometimes has his own thoughts. He falls back into heroism when Laurie and him decide to take Archie out and then happens to see a burning building. He did not leave with the intention of doing something heroic. Similarly, he wasn’t the one investigating the killings, but he does get Rorschach out of prison, seemingly only so he continue his new-found confidence. But the end is the real killer (pun intended), because he ultimately accepts Veidt’s plot and Dr. Manhattan’s murder of his crime-fighting partner.

Rorschach was a psychopath who handed out judgments too severely. His understanding of humanity is as far-off as Dr. Manhattan’s. It is easier to like him because he is the only hero who wants to be a hero for the same reason as the Dark Knight, and that desire to right wrongs is something I think most people admire. He also has the best line in the entire Graphic Novel when in prison: “None of you understand. I’m not locked up in here with you; you’re locked up in here with me.” But he crosses a line that the Dark Knight was careful not to cross; he kills people, and does so with a vengeance. He seems to think that killing people is the only way to deal justice and he constantly takes note of any small moral infraction. It is strange to me, then, that he is the one who cannot accept Veidt’s plot. He seems to be the only one who we are set up to believe would accept it.

Moore has set me up to think that I will like some of the characters, but he has left me in the lurch. I’m certain it’s on purpose.

Rorschach’s Image of Haunting Embrace

Rorschach, also known as Walter Kovacs, seems morally frozen in his stances of what is good and what is evil. Rosen speaks to this as she states, “Rorschach is the dark side of nostalgia” and “It is clear that Moore and the creators meant for us to read Rorschach as the vessel of an outdated morality” (90). The morality in Rorschach’s view of the world not only pertains to how he judges things in his life, but how he perceives visual images as well, especially the image that is often repeated in his life, the one of distorted intimacy in a couple’s embrace.

Walking in on his mother having sex was to him a source of “Dirty feelings, thoughts and stuff” which “upset him, physically” and made him “feel bad just talking about it” (6:32). While he seems to want to avoid the subject of the “Siamese twins, joined at the face and chest and stomach,” he cannot escape the imagery as he sees it splashed in his vision at any sight of intimacy (6:32). He psyche is scarred by the scene of his mother with that man who was a stranger to him and the subsequent trouble he gets into from breaking up their brief union. It seems so scarred that, in Rorschach’s mind, all instances of intimacy or of romantic embrace is now deemed to be solely on the side of evil, or if it is not that far, it is surely a sign of immediate discomfort when Rorschach sees these encounters.

This can be seen when he sees the silhouette of a couple in a doorway. Immediately, Rorschach’s response is “Didn’t like it, makes the doorway look haunted,” as seen in the picture below. The image is echoed so often when dealing with Rorschach that it sees like the word “scarred” wouldn’t do his mental disposition justice. “Haunted,” as he put it, would seem more appropriate.

Yet, the ghost is also catching. Following the lover’s inkblot and Rorschach’s story from his childhood, Rorschach’s therapist’s mind view becomes considerably altered by his time with Rorschach (6:3). Dr. Malcolm Long’s marriage deteriorates. He is distracted, almost consumed by his need to understand Rorschach and his obsession with being Rorschach instead of Walter Kovacs. I say it is catching because the therapist seems to have caught the image of intimacy that echoes so often with Rorschach. The therapist sees two people embracing in an image of graffiti, and his comment about them is that “On 7th Avenue, the Hiroshima lovers were still trying inadequately to console one another” (6:27). He may not be as haunted as Rorschach is by the image, but he does view the embrace as “inadequate,” which may be also echoed in the subsequent problems of his marriage.

The haunting image seems so engraved in Rorschach that it becomes a part of him. This can be seen near the end of Watchmen, when Rorschach sees Laurie and Dan embracing after hearing Veidt’s plot. The distorted image of the couple’s embrace that has been following him throughout the novel is displayed on his mask immediately following him seeing the two together. He himself displays the image, only to have it disappear right after.

It would seem that the image of the couple is a visible marker of both Rorschach’s possibly instability when it comes to looking at the world and his distorted view of intimacy in general based on his upsetting childhood.

~Kelley

Endearing Menace

Breathing life into the only dynamic character in Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, Miller allows us to “hear” Bruce Wayne’s first-person narrative as an insightful running dialog between the person he once was and the person he has become. Wayne’s metastatic attitude toward the conditions of Gotham, a city he must both love and hate, keep him from focusing on the moral dilemma of sacrificing the few to save the many . Wayne’s metatextual comments assist the narrative as much as they reveal his provocative thoughts toward the criminals he seeks to annihilate. Wayne’s thinking is self-centered, and, of course, more appealing as the unconventional superhero. Gordon and Superman’s characters’ embody compassion and remain static throughout the novel. This is not a bad thing.

Breathing life into the only dynamic character in Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, Miller allows us to “hear” Bruce Wayne’s first-person narrative as an insightful running dialog between the person he once was and the person he has become. Wayne’s metastatic attitude toward the conditions of Gotham, a city he must both love and hate, keep him from focusing on the moral dilemma of sacrificing the few to save the many . Wayne’s metatextual comments assist the narrative as much as they reveal his provocative thoughts toward the criminals he seeks to annihilate. Wayne’s thinking is self-centered, and, of course, more appealing as the unconventional superhero. Gordon and Superman’s characters’ embody compassion and remain static throughout the novel. This is not a bad thing.

Dictated by the violence of his past and by the fierce rampage of helplessness he feels for the loss of a functional, loving world, Wayne is looked at as either a “crusader or [a] menace” (49). After the Joker kills over a hundred people in the audience of a night time talk show, Wayne expresses the futility of trying to take on criminals and the public together: “Every year they grow smaller. Every year they hate us more” (129).

Paradoxically, Commissioner Gordon has tremendous concern for the public safety, but he does not blame society as a whole. In fact, he worries repeatedly that after he retires his lack of influence and power will result in more chaos, violence and destruction to Gotham. Here we see the difference between Batman and Gordon. We readily recognize that authorial intention is aimed at keeping the city safe; the dichotomy of how Miller represents these two points of view on method and outcome complicate the characterization of Batman and foreshadow violence for the future.

Nothing to Reflect on in DKR

The DKR is intense. Almost too intense. The violence, either in the dialog or in the illustrations, never stops. There is no time to pause and reflect– is there a reason? There are interjections by the “media” that, at first, I thought served as a humorous commentary on violence. They are funny, but they appear to be there only to move the plot along and illuminate, in case we don’t understand, what we’ve just read. They have a plot and momentum all their own. Besides these instances of comic relief, there are even fewer moments of compassion and tenderness. Mainly though, DKR is violence: open the book to any page and find never ending mayhem and carnage. This is what we expect from anything in the universe of Batman.

We have black people and hints of gayness, alcoholism, drug addiction, and transgender villainy – all reflections of our “time”. But other than these, it appears that the “Comic Code” prevails in DKR. A flawed man is redeemed. The wicked are punished. The Batman doesn’t attempt depth. Life for Miller, at least reflected in his work, is a simple binary.

There are no surprises in DKR. We know what we are getting from the moment we begin. Adversaries change and grow; some are more colorful and kinkier that others, but in the end, good triumphs and evil is vanquished. Life goes on until the next time. In the Sharrett interview, Miller says that DKR is not pessimistic because the “good guy wins.” We knew that from the outset. How else could it possibly end?

As a kid I liked it a lot. I like it now, but not so much. It wears me out. It quickly grows stale. Maybe that is the reason for the intensity and violence. It hides the fact that there is really nothing to reflect on in DKR.

Miller, impossible reversals, and masculinity (also in this issue: splash pages)

1.

I must confess. The only Frank Miller I’ve really been able to enjoy is Batman: Year One. Reasons for this disconnect no doubt abound, from the objectification of women and sadism that pervade All-Star Batman and Robin the Boy Wonder to the deliberate discursiveness and unanswered continuity questions of The Dark Knight Returns, from the sheer brutality of his pencils in 300 to the bizzare nature of the coloring in The Dark Knight Strikes Again. However, I believe one of the most fundamental problems I hit consistently is Miller’s consistent portrayal of the impossible reversal, and the clearly heroic masculinity idealized in this recurring device.

This device occurs four times in The Dark Knight Returns. An emotional version appears (pp. 17-20) when Bruce Wayne recalls the the genesis of his obsession with the image of the bat. His first battle with the Mutants leader fleshes out the structure in physical, brutal life (pp. 77-83), as does the battle between Batman and the Joker (pp. 143-151). Lastly, the fight with Superman somewhat subverts the trend, albeit with an even more impossible reversal in the form or chemically faked death and resurrection. Miller’s fixation on this device as an indicator of heroic masculinity appears in the Sin City story The Yellow Bastard, in which the main character saves himself from being hanged by tensing his neck muscles after the hanging has actually taken place.

The two middle battles, with the Mutants leader and the Joker, present the most solid embodiment of the trope in The Dark Knight Returns. In both, Batman faces defeat at the hands or plans of his foe. Despite being for all intents and purposes defeated, he pushes through the pain and wrestles victory into his grasp (all narrated quite grimly in Miller’s trademark neo-noir monologue). The connection I make between these impossible reversals and Miller’s idealized heroic masculinity come in the word choices and imagery chosen to go along with the action. In the battle with the Mutants leader, the monologue constantly drips with almost sensual joy in combat – “A BEAUTY to his SOLAR PLEXUS,” “BONE bites into my KNUCKLES” – not to mention the aggressively (and in my view sadistic) domineering view Batman takes of the fight. His focus on the fight is forcing his opponent to take his orders – “I make him eat some GARBAGE—-then I help him SWALLOW it,” “SHOW me EXACTLY how MUCH it takes to BREAK YOU,” “Least I can do – is shut him UP,” “Teach him brand-new KINDS of pain” – all creating a hypermasculine view of a hero who teaches evildoers that they cannot act as they want in HIS world. Combined with the overmuscled, triangular torsoed Batman images which continue to dominate the panels, Miller’s hero in The Dark Knight Returns emerges as a physically perfect (not to say impossible, considering Batman’s ostensible age at the time of the story), paternalistic pedagogue who delights in pain both to himself and others, considering it the mark of a true, manly hero.

Though I’m not sure I can completely assimilate Alan Moore’s vision in Watchmen (and apparently, he doesn’t either, since he went on to write Tom Strong and other extremely idealistic versions of superheros), I find his depiction of Rorschach acting out the same basic pattern on taking impossible amounts of pain and overcoming them as suicidally insane, rather than heroically masculine a less troubling portrayal.

It does occur to me that in the two instances I examine here, Batman actually requires saving from his situation from the petite, female Robin. So it’s possible (if unlikely in my mind, given the other instance of the trope in Miller’s other work) that Miller is actually attempting to subvert the trope. I remain unconvinced and unallured.

2.

Looking at The Dark Knight Returns for recurring formal elements, I noticed the consistent placement of splash pages (a page in which the panel is either the whole or almost the whole of the page) on the left side, in a consistent pose of heroism which often contrasts with the actual narrative point, such as Batman holding the suicide general wrapped in a flag, the pose and colors superficially suggesting honor to a fallen soldier, the details pointing to Batman’s contempt instead. The image of Robin hugging the wounded Bruce Wayne confuses with the combination of tenderness of action and harshness of pose (mitigated somewhat by Wayne’s small smile, without cruelty for once), and most of the panels with Superman (unsurprising, given Miller’s take on Superman as a naive sellout) which undercut his pose with the real meaning of his action, or a metaphoric commentary, such as the image of him lifting the tank suggesting the taint and burden he bears of all the war and death cause by his acquiescence to the powers that be.