Something about David Denby’s review of Iron Man in The New Yorker has been bothering me ever since I saw the film for myself. I’ve finally figured out it has to do with Denby’s misreading of the superhero genre, rooted in a disregard — shared by many critics and moviegoers — of the source material for superhero movies, that is, comic books.

Now, I am not a Marvel fanboy, and I definitely never was an Iron Man fan. But I still feel the need to come to director Jon Favreau’s defense here and respond to Denby’s review, if only because the review has resumed a conversation that has been going on in fits and starts in my mind since the first Spider-Man movie in 2002.

Two elements of Iron Man are particularly susceptible to the general misunderstanding of the comic book form that is so widespread: Robert Downey, Jr.’s eyes and Tony Stark’s heart.

About Downey’s eyes, Denby comments that

…once Stark climbs inside and becomes Iron Man he loses his perverse charm; Downey without eyes is Downey cancelled.

True, there is something transfixing about the glint in Downey’s eyes. And true, this glint disappears behind the mask. But this is the inherent nature of the superhero genre: an appealing character must don a mask, hiding the very bodily feature that film has taught us, through the widespread use of the close-up, is the indicator of emotion — the face.

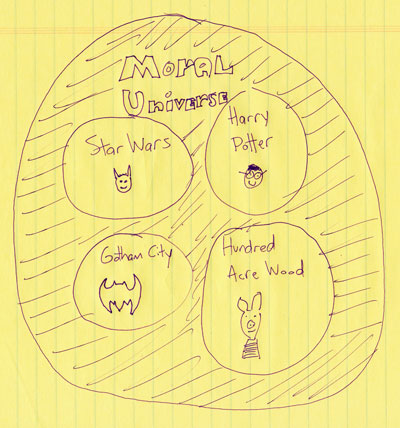

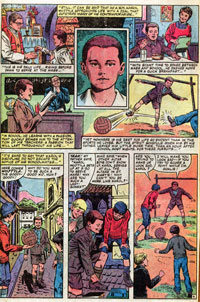

In comic books, it’s a different story. Because all the images are still images, the hero with a mask is on the same plane as the hero without a mask. Emotions are conveyed, not through facial close-ups, but through the artwork itself: slanted or jagged lines, scenes exploding into the gutter, full-page panels that slow down reading, and so on.

A superhero movie with a hero whose face is static behind a mask — Batman, Spider-Man, and yes, Iron Man — is actually an homage to the source of the film. The masked superhero whose expressions are inscrutable is “quoting” the form of the comic book. In her studies of film adaptations of literary works, the film theorist Millicent Marcus has coined the term “umbilical scene” to describe such tributes: a conscious or unconscious acknowledgment by the film of its literary “mother.” In superhero movies, these umbilical scenes can be predictable in-jokes, such as the Stan Lee cameo in every movie based on a Marvel character. Or they can harder-to-decipher formal decisions, such as the unmoving mask.

The first umbilical scene I ever noticed in a Marvel-universe movie was the absolutely inanimate mask of the Green Goblin in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man. The effect was actually disconcerting, to see this supervillain speak from behind a frozen face. I first thought the Green Goblin’s mask was some sort of play on Japanese Noh theater, but I realized soon after that Willem Dafoe’s Green Goblin, even more so than Spidey in the film, was a conscious recognition of Spider-Man’s origins in the stock-still pages of a comic book.

The second element of Iron Man that Denby gets wrong is that “Tony Stark is more like James Bond — he’s always on top.” Again, I’m no fanboy, but I have to point out that Denby glosses over Stark’s fatal flaw: his injured heart, which comes into play on both literal and metaphoric levels in the film. The archetypal superhero must have a weakness. Superman has his kryptonite. Peter Parker has his Aunt May, and Iron Man has his heart, which is seconds away at any given moment from being shredded internally by the shrapnel in his veins.

In terms of Achilles’ Heels, Stark’s heart is a much richer narrative device than, say, a rock from the planet Krypton. There’s a very neat internal/external dichotomy going on with Stark. There’s the obvious and surface-level theme of physical vulnerability, staved off through engineering and technology. But there’s also the symbolic nature of the tender heart, surrounded by armor — that is, Stark builds barriers to protect what turns out to be a fragile emotional interior.

I don’t know where the inevitable Iron Man franchise of films will go, but if they follow the comic books even remotely, they will have to reckon with (1) Stark’s damaged heart, always threatening to “crash” in a more profound way than any cybernetic exoskeleton might and (2) the dark side of Stark’s “James Bond” style of living, which manifests itself in the comic books as depression and alcoholism.

With these dangers on the horizon, and only a metal suit to protect himself, Tony Stark cuts a much more interesting figure than most superheroes. And I’m looking forward to what happens next, Avengers Initiative or not…

by Scott McCloud

by Frank Miller

by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

by Art Spiegelman

by Chris Ware

by Gene Luen Yang

by Marjane Satrapi

by Wilfred Santiago

by Alison Bechdel