Anybody who follows Facebook has probably heard about the user who found it impossible to delete his account; even after he deactivated his profile, it showed up in searches and various Facebook news feeds.

If you can’t get out of Facebook when you’re alive, what happens when you die?

What happens to your Facebook profile when you die?

Sadly, this is not a rhetorical question. I’ve had two Facebook friends—first a colleague (and true friend) and second a former student last month—pass away. Yet their Facebook pages persist, digital ghosts with mini-feeds still growing, updated with the usual nonsense and noise (“Mike joined the group Free David Hasselhoff” and “Barrald Terrence and Will Navidson are now friends”) that fill anybody’s Facebook feeds.

In fact, in the second case, I only found out about my student’s death from a terse, surreal update to her profile by a family member, which then showed up in my Facebook news feed. Her Facebook profile has since become a kind of memorial, with dozens of friends writing their goodbyes on her “wall.”

In the first case, nobody has written on my friend’s wall in the six months since he died, though he was loved and respected by hundreds of people across the country. I suspect the difference between my student and my friend’s post-mortem Facebook activity is generational; digital mourning, at least in a consumer-oriented space like Facebook, is considered insensitive or insincere by anyone over the age of 30. And so my friend’s profile is eerily silent, his feed simply stating with no irony that he “has no recent activity.”

I imagine that eventually Web 2.0 will catch up with real life and incorporate grieving into its ecological landscape. Maybe this will be the beta version of Web 3.0.

I don’t know which is creepier: a Facebook engine that doesn’t know when we die and carries on as if we hadn’t; or a Facebook engine that somehow taps into public records and newspaper obituaries, detecting when we die, and initiates a sort of prescribed last will and testament profile update, a more tactful 404 error message.

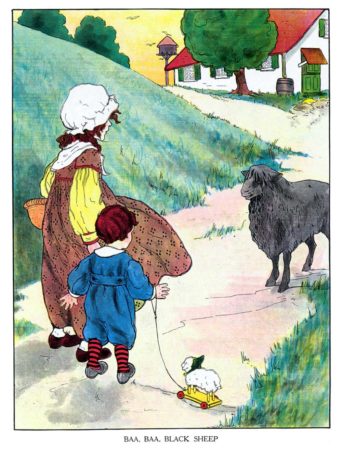

For Christmas, I gave my son a new edition of the classic The Real Mother Goose, with illustrations by Blanche Fisher Wright. First published in 1916, the book has been a perennial childhood favorite for almost a century. It certainly was one of mine. And so it was with nostalgia that I began reading “Little Bo-Peep” on the first page. An hour later, I had read maybe a hundred more nursery rhymes to my son, who couldn’t get enough.

For Christmas, I gave my son a new edition of the classic The Real Mother Goose, with illustrations by Blanche Fisher Wright. First published in 1916, the book has been a perennial childhood favorite for almost a century. It certainly was one of mine. And so it was with nostalgia that I began reading “Little Bo-Peep” on the first page. An hour later, I had read maybe a hundred more nursery rhymes to my son, who couldn’t get enough.