It seems that public opinion is shifting toward the idea that Tony Soprano was whacked in The Sopranos series finale after the screen went black. That possibility can never entirely be ruled out, which is part of the brilliance of the abrupt, unsatisfying final seconds of the series.

I want to suggest, however, that the blank screen signifies something other than Tony’s death.

In fact, the final seconds of a black screen forever hold Tony’s death in abeyance. It can never happen now. But more fundamentally, the sudden disruption of the Journey song, the disconcerting jump cut to the black screen—these remind us that we are watching television, that our visit with Tony has been mediated all along. Think of the the sudden silence and black screen as a kind of Brechtian moment of estrangement, shocking the viewer out of the usual mode of passive consumption.

We might think of the entire episode (called “Made in America”) as a contemplation upon the habits of the television-watching public. Upon a second viewing, this theory seems obvious, as multiple times we either catch characters on The Sopranos watching television themselves or we the viewers are forced to watch a TV within a TV:

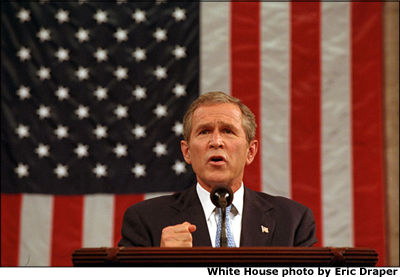

What to make of all this, aside from the commonplace grievance that our lives are mediated, that representation has replaced reality? I think Chase is doing something far more politically charged here. Note that the final shot of a television shows President Bush, famously dancing in April 2007. Chase is clearly mocking Bush, who becomes a Nero figure, fiddling while Rome burns to the ground. When you consider the dozens of references to the War in Iraq and the deadly SUVs in this episode (the Ford Expedition smashing Leotardo’s skull and A.J.’s firebomb of an Xterra), it doesn’t take much to imagine that Chase is making some very serious indictments about American arrogance and American hypocrisy, embodied in everyone from President Bush down to Anthony Soprano, Jr.

What to make of all this, aside from the commonplace grievance that our lives are mediated, that representation has replaced reality? I think Chase is doing something far more politically charged here. Note that the final shot of a television shows President Bush, famously dancing in April 2007. Chase is clearly mocking Bush, who becomes a Nero figure, fiddling while Rome burns to the ground. When you consider the dozens of references to the War in Iraq and the deadly SUVs in this episode (the Ford Expedition smashing Leotardo’s skull and A.J.’s firebomb of an Xterra), it doesn’t take much to imagine that Chase is making some very serious indictments about American arrogance and American hypocrisy, embodied in everyone from President Bush down to Anthony Soprano, Jr.

Add in the fact that the only things the characters watch more intently in this episode than television sets are gas stations (where Leotardo might use a pay phone), and we have an explicit political statement about Bush’s follies abroad:

The juxtaposition of the American flag and the Gulf truck is surely intentional. As is the display of the American flag every other time in the episode a gas station appears.

Chase seems to be proposing an antidote to the Bush administration’s own mediation of itself, which links Bush to patriotism by always placing him near a Stars and Stripes.

By replacing Bush with the gas station, Chase lays bare the nature of the relationship between the United States and the War in Iraq. It is about oil.

But to say this is to say nothing new. So Chase makes it fresh by making it subtle. He again catches us off guard—so focused are we on those 11 seconds of black space where Tony and his family should be at the end of the episode, we do not recognize what’s really going on. Instead of asking what happens to Tony, we should be asking why are there seven flags at this gas station?