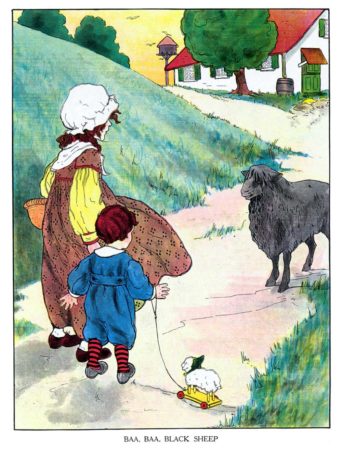

For Christmas, I gave my son a new edition of the classic The Real Mother Goose, with illustrations by Blanche Fisher Wright. First published in 1916, the book has been a perennial childhood favorite for almost a century. It certainly was one of mine. And so it was with nostalgia that I began reading “Little Bo-Peep” on the first page. An hour later, I had read maybe a hundred more nursery rhymes to my son, who couldn’t get enough.

For Christmas, I gave my son a new edition of the classic The Real Mother Goose, with illustrations by Blanche Fisher Wright. First published in 1916, the book has been a perennial childhood favorite for almost a century. It certainly was one of mine. And so it was with nostalgia that I began reading “Little Bo-Peep” on the first page. An hour later, I had read maybe a hundred more nursery rhymes to my son, who couldn’t get enough.

For a long time I had heard that many popular nursery rhymes were rooted in historical events or based on historical figures. The best known example is “Ring around the Rosey”–supposedly about the plague, although there is little evidence to support such an interpretation. “Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary” is another nursery rhyme that seems to point to a real person, although whether it refers to Mary Queen of Scots or Queen “Bloody Mary” of England is debated.

Regardless of whether nursery rhymes have specific historical antecedents, I have to say, with my nostalgia tinged by a critical eye, that they certainly are about more than just sing-songy rhythms and rhymes.

It’s surprising exactly how many deal with death. There’s “Solomon Grundy,” an old favorite of mine:

Solomon Grundy,

Born on a Monday,

Christened on Tuesday,

Married on Wednesday,

Took ill on Thursday,

Worse on Friday,

Died on Saturday,

Buried on Sunday.

This is the end

Of Solomon Grundy.

Here death is front and center, or at least as equal a part of life as, well, life. Grundy has three days to live healthy, happy, and wise (Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday), and his downhill spiral, beginning with a mysterious illness on Thursday, takes three days as well (Thursday, Friday, and the death rattle on Saturday). Sunday (born) bookends Monday (died), and the final pair of lines summarizes the story so far: the end is final and inevitable.

But maybe it’s not surprising that death is so central to these nursery rhymes. Death was more a part of daily life in the formative years of Mother Goose (in the 17th century) than now, when we shuffle off our sick and our dying to hospitals and hospices and strive to eliminate the specter of death from modern life. I’m reminded of a remark by Walter Benjamin, who suggests that one of industrialized society’s subconscious goals has been “to make it possible for people to avoid the sight of the dying.” Benjamin continues:

Dying was once a public process in the life of the individual and a most exemplary one; think of the medieval pictures in which the deathbed has turned into a throne toward which the people press through the wide-open doors of the death house. In the course of modern times dying has been pushed further and further out of the perceptual world of the living. There used to be no house, hardly a room, in which someone had not once died. (Illuminations 93-94)

Solomon Grundy is a holdover from those days, when everybody died and everybody knew it and everybody saw it.

To be sure, we have death today, but it’s nearly always either spectacular death (an execution caught on a mobile phone, a CGI explosion in a Hollywood blockbuster) or mass death (tsunami victims piled high, mass graves outside a desert village). But ordinary deaths, the Solomon Grundy’s of the world dying dignified at home, surrounded by friends and family. Does anybody experience this any more? “Today people live in rooms that have never been touched by death,” Benjamin writes. He calls these people, these living who do not see dying as part of life, “dry dwellers of eternity.”

Benjamin seems to be saying that death quenches the dry desert of eternity. To be touched by death is to be touched by life. To be touched by death is to be full of life.