I’m spending July in Cádiz, Spain, with my family and a bunch of students from Davidson College. The other weekend we visited Granada, home of the Alhambra. Built by the last Arabic dynasty on the Iberian peninsula in the 13th century, the Alhambra is a stunning palace overlooking the city below. The city of Granada itself—like several other cities in Spain—is a palimpsest of Islamic, Jewish, and Christian art, culture, and architecture.

Take the streets of Granada. In the Albayzín neighborhood the cobblestone streets are winding, narrow alleys, branching off from each other at odd angles. Even though I’ve wandered Granada several times over the past decade, it’s easy to get lost in these serpentine streets. The photograph above (Flickr source) of the Albayzín, shot from the Alhambra, can barely reveal the maze that these medieval Muslim streets form. The Albayzín is a marked contrast to the layout of historically Christian cities in Spain. Influenced by Roman design, a typical Spanish city features a central square—the Plaza Mayor—from which streets extend out at right angles toward the cardinal points of the compass. Whereas the Muslim streets are winding and organic, the Christian streets are neat and angular. It’s the difference between a labyrinth and a grid.

It just so happened that on our long bus ride to Granada I finished playing Anchorhead, Michael Gentry’s monumental work of interactive fiction (IF) from 1998. Even if you’ve never played IF, you likely recognize it when you see it, thanks to the ongoing hybridization of geek culture with pop culture. Entirely text-based, these story-games present puzzles and narrative situations that you traverse through typed commands, like GO NORTH, GET LAMP, OPEN JEWELED BOX, etc. As for Anchorhead, it’s a Lovecraftian horror with cosmic entities, incestual families, and the requisite insane asylum. Anchorhead also includes a mainstay of early interactive fiction: a maze.

Two of them in fact.

It’s difficult to overstate the role of mazes in interactive fiction. Will Crowther and Don Woods’ Adventure (or Colossal Cave) was the first work of IF in the mid-seventies. It also had the first maze, a “maze of twisty little passages, all alike.” Later on Zork would have a maze, and so would many other games, including Anchorhead. Mazes are so emblematic of interactive fiction that the first scholarly book on the subject references Adventure‘s maze in its title: Nick Montfort’s Twisty Little Passages: An Approach to Interactive Fiction (MIT Press, 2003). Mazes are also singled out in the manual for Inform 7, a high level programming language used to create many contemporary works of interactive fiction. As the official Inform 7 “recipe book” puts it, “Many old-school IF puzzles involve journeys through the map which are confused, randomised or otherwise frustrated.” Mazes are now considered passé in contemporary IF, but only because they were used for years to convey a sense of disorientation and anxiety.

And so, there I was in Granada having just played one of the most acclaimed works of interactive fiction ever. It occurred to me then, among the twisty little passages of Granada, that a relationship exists between the labyrinthine alleys of the Albayzín and the way interactive fiction has used mazes.

See, the usual way of navigating interactive fiction is to use cardinal directions. GO WEST. SOUTHEAST. OPEN THE NORTH DOOR. The eight points of the compass rose is an IF convention that, like mazes, goes all the way back to Colossal Cave. The Inform 7 manual briefly acknowledges this convention in its section on rooms:

In real life, people are seldom conscious of their compass bearing when walking around buildings, but it makes a concise and unconfusing way for the player to say where to go next, so is generally accepted as a convention of the genre.

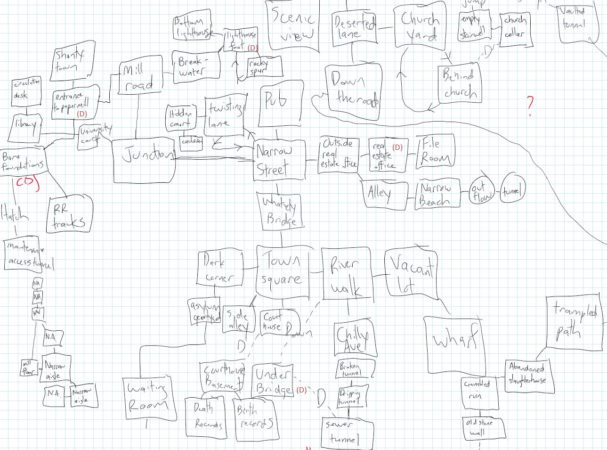

Let’s dig into this convention a bit. Occasionally, it’s been challenged (Aaron Reed’s Blue Lacuna comes to mind), but for the most part, navigating interactive fiction with cardinal directions is simply what you expect to do. It’s essentially a grid system that helps players mentally map the game’s narrative spaces. Witness my own map of Anchorhead, literally drawn on graph paper as I played the game (okay, I drew it on OneNote on an iPad, but you get the idea):

And when IF wants to confuse, frustrate, or disorient players, along comes the maze. Labyrinths, the kind evoked by the streets of the Albayzín, defy the grid system of Western logic. Mazes in interactive fiction are defined by the very breakdown of the compass. Direction don’t work anymore. The maze evokes otherness by defying rationality.

When the grid/maze dichotomy of interactive fiction is mapped onto actual history—say the city of Granada—something interesting happens. You start to see the the narrative trope of the maze as an essentially Orientalist move. I’m using “Orientalist” here in the way Edward Said uses it, a name for discourse about the Middle East that mysticizes yet disempowers the culture and its people. As Said describes it, Orientalism is part of a larger project of dominating that culture and its people. Orientalist tropes of the Middle East include ahistorical images that present an exotic, irrational counterpart to the supposed logic of European modernity. In an article in the European Journal of Cultural Studies about the representation of Arabs in videogames, Vít Ŝisler provides a quick list of such tropes. They include “motifs such as headscarves, turbans, scimitars, tiles and camels, character concepts such as caliphs, Bedouins, djinns, belly dancers and Oriental topoi such as deserts, minarets, bazaars and harems.” In nearly every case, for white American and European audiences these tropes provide a shorthand for an alien other.

My argument is this:

- Interactive fiction relies on a Christian-influenced, Western European-centric sense of space. Grid-like, organized, navigable. Mappable. In a word, knowable.

- Occasionally, to evoke the irrational, the unmappable, the unknowable, interactive fiction employs mazes. The connection of these textual mazes to the labyrinthine Middle Eastern bazaar that appears in, say Raiders of the Lost Ark, is unacknowledged and usually unintentional.

- We cannot truly understand the role that mazes play vis-à-vis the usual Cartesian grid in interactive fiction unless we also understand the interplay between these dissimilar ways of organizing spaces in real life, which are bound up in social, cultural, and historical conflict. In particular, the West has valorized the rigid grid while looking with disdain upon organic irregularity.

Notwithstanding exceptions like Lisa Nakamura and Zeynep Tufekci, scholars of digital media in the U.S. and Europe have done a poor job looking beyond their own doorsteps for understanding digital culture. Case in point: the “Maze” chapter of 10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10 (MIT Press, 2012), where my co-authors and I address the significance of mazes, both in and outside of computing, with nary a mention of non-Western or non-Christian labyrinths. In hindsight, I see the Western-centric perspective of this chapter (and others) as a real flaw of the book.

I don’t know why I didn’t know at the time about Laura Marks’ Enfoldment and Infinity: An Islamic Genealogy of New Media Art (MIT Press, 2010). Marks doesn’t talk about mazes per se, but you can imagine the labyrinths of Albayzín or the endless maze design generated by the 10 PRINT program as living enactments of what Marks calls “enfoldment.” Marks sees enfoldment as a dominant feature of Islamic art and describes it as the way image, information, and the infinite “enfold each other and unfold from one another.” Essentially, image gives way to information which in turn is an index (an impossible one though) to infinity itself. Marks argues that this dynamic of enfoldment is alive and well in algorithmic digital art.

With Marks, Granada, and interactive fiction on my mind, I have a series of questions. What happens when we shift our understanding of mazes from non-Cartesian spaces meant to confound players to transcendental expressions of infinity? What happens when we break the convention in interactive fiction by which grids are privileged over mazes? What happens when we recognize that even with something as non-essential to political power as a text-based game, the underlying procedural system reinscribes a model that values one valid way of seeing the world over another, equally valid way of seeing the world?

Header Image: Anh Dinh, “Albayzin from Alhambra” on Flickr (August 10, 2013). Creative Commons BY-NC license.