I’ve got two fantastic advanced literature classes planned for Fall 2009:

ENGL 459 (Disaster Fiction)

This class explores what the influential critic and novelist Susan Sontag called “the imagination of disaster.” Sontag was speaking of Hollywood cinema of the fifties and sixties, arguing that end-of-the-world films of this era simultaneously aestheticize destruction and address a perversely utopian impulse for moral simplification. But what about disasters in contemporary fiction? While natural and unnatural disasters have provided Hollywood with predictable script material for decades, less familiar are the meditations on disasters that serious novelists have taken up in literary fiction. In this class we will consider how novelists imagine disaster. From uncontrollable natural disasters to planned nuclear annihilation, from swift destruction unleashed by human avarice to the slow death of a dying world, we will examine the ways fiction reaffirms, questions, or rewrites the modalities of disaster. Along the way we will consider the social, historical, and political contexts of disaster fiction, exploring what it means to “think the unthinkable” in different times and places. Among the writers we will study are Margaret Atwood, Don DeLillo, Ursula Le Guin, Cormac McCarthy, W.E.B. DuBois, and many others.

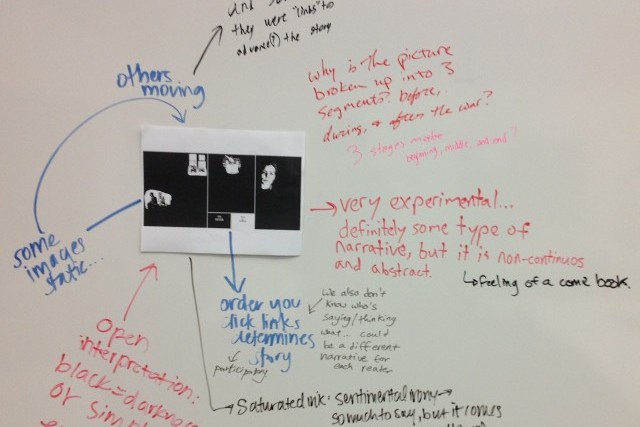

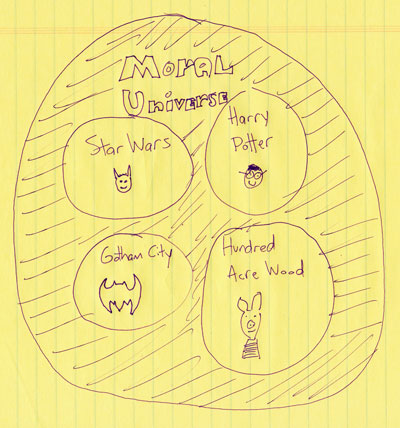

ENGL 493 (The Graphic Novel)

This course considers the storytelling potential of graphic novels, an often neglected form of artistic and narrative expression with a long and rich history. Boldly combining images and text, graphic novels of recent years have explored divisive issues often considered the domain of “serious” literature: immigration, racism, war and terrorism, sexual abuse, and much more. Informed by literary theory and visual culture studies, we will analyze both mainstream and indie graphic novels. In particular, we will be especially attentive to the unique visual grammar of the medium, exploring graphic novels that challenge the conventions of genre, narrative, and high and low culture. While our focus will be on American graphic novelists, we will touch upon artistic traditions from across the globe. Graphic novelists studied may include Kyle Baker, Alison Bechdel, Alan Moore, Wilfred Santiaga, Marjane Satrapi, Art Spiegelman, and Gene Luen Yang.