Well done earlier posters on getting to some of the big issues early. As a result, I’m going to focus on one aspect of Jimmy Corrigan I found fascinating (but probably wouldn’t have blogged on as a first choice): the introduction.

Perhaps it’s better referred to as a primer than an introduction. Or an introduction to reading comics. Either way, Ware’s playfulness in this section actually helps reveal a lot about the text as a whole. His intricate and elegant language (especially in the third section, as Lars mentioned on twitter) help set a tone oft-repeated (and drawn) throughout the book. And just as importantly, his primer to comics, including the “how to read these/do you see a mouse or just lines in the box” section and the short quiz, help reveal his expectations of his readers, and some preconceptions that permeate the comic world.

On a side note, another reason I’m compelled to work with the introduction this week: no page numbers.

Jared’s directions to find the text he’s referencing in this week’s post:

1. Open front cover. 2. Stop.

If you’re like me, maybe you skipped over what looked to be a silly part of the book and just dove right into the text. If you’re like me, you may have found yourself gloriously lost by about page 30 and decided that perhaps returning to the introduction might help sort things out. In my experience, the introduction was not nearly as helpful as the first and only recap when it came to making sense of the multiple threads in JC, but the introduction was still an interesting and informative read that bears heavily on the remainder of the text.

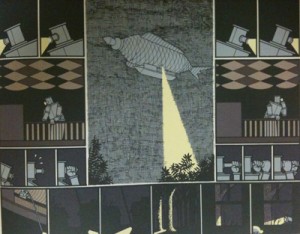

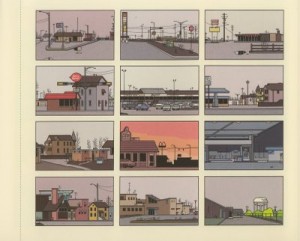

Ware starts by outlining a brief history of visual storytelling, much like we did our first week in class. One thing I think this does is open the table for the possibilities that come with telling stories with pictures. Cavemen did it one way, paintings of the Renaissance another, and “comic books” still another. Looking back on this now, it’s almost as if Ware is spelling out a warning: this will not be like any other “comic book” you have read. And Jimmy Corrigan isn’t like any other comic book I’ve read. Panels only sometimes have a clearly defined direction, thanks to the arrows, and as others have mentioned, dreams, past stories and the present story form an interwoven story that can get really confusing. Like Ulysses confusing.

Moving on to section 2, Ease of Use, we begin to see even more of the funny tone Ware brings. Here the ease of use has nothing to do with reading (which he handles in general instructions), but the ease of portability, and convenience to transport and read the book as you please. But this does not mean this will be an easy book to read, just an easy book to carry around and read as you wait. When it comes to the actual reading experience, it’s best to read the first line of the introduction:

“While it was not the intention of the author of this publication to produce a work which would in any way be considered “difficult,” “obscure,” or, even worse, “impenetrable,” it has come to the attention of our research faculty that some readers, owing to an (entirely excusable) unfamiliarity with certain trends and fads which flow through the tributaries of today’s ” cutting-edge culture,” might not be suitably equipped to sustain a successful linguistic relationship with the pictographic theater it offers.” Again, it’s important to remember the tongue-in-cheek nature of this entire piece, but at the same time to recognize some of the kernals of truth he drops. I’m somewhat familiar with comics, but my ‘linguistic relationship’ with this ‘pictographic theater’ was frequently strained, rarely sustained. Thanks for the warning, Ware. I just wish I’d taken it more to heart. In this sense, JC is easy to use (as a book is used), but not easy to comprehend/follow. At least not without a lot of work.

I will move on to the third section now, then leave sections 4 and 5 open for comments since they also help reveal some of the themes and difficulties presented in JC.

My only note for Section 3, “Role,” is scribbled at the top of the page. It reads: “awesome.” No, this note is not very deep, nor is it very scholarly. In my defense there’s not a lot of room for notes here, and I dislike the notion of writing in any graphic novel, even if it’s just the introduction. This section blew me away. It was more than just hilarious, profound writing as the importance of a line such as: “As such, the thinking person would have to conclude that, in general, the seeking of of emotional empathy in art is essentially a fool-hardy pursuit, better left to the intellectually weak, or to the ugly, for they have nothing else with which to occupy themselves. Besides, it is unsightly to feel sorry for oneself, and such ‘unfortunate times’ eventually pass, anyway, and if they don’t, then mercifully, for the rest of us at least, suicide is, of course, an option.”

This one line is incredibly loaded, and has implications for our entire reading. Is Ware talking about himself here? We know Jimmy is somewhat based on him, and this line seems to directly reference the lonely, sad, pathetic, passive, ugly, intellectually weak main character in the novel. Jimmy frequently feels sorry for himself, or at least that’s how I’ve read his character, and that is unsightly. At least there’s always suicide. At the same time, though, some of my previous tongue-in-cheek questions come back into play in this section. I don’t think it’s complete farce, but I also don’t think Ware intends us to take it as fact. It falls somewhere in between, and I’m still trying to understand how, exactly, I should be reading this.

For example, Ware writes that emotional empathy is a foolhardy pursuit. Now, as far as Jimmy Corrigan goes, I agree. I can’t empathize with this character, and after a point I stopped trying and just started enjoying the interesting way he goes about creating a comic narrative. But I can’t say this is the case for 99% of the other fiction I’ve read. Any good writer knows that if you don’t have a character people can relate to (think empathize with), then you don’t really have a good story. That’s not to call Ware a bad writer, he just fits into the echelon of folks who buck the rules, and somehow make it work anyway. They’re a class all their own. Does he know this? I feel like he must, and that’s what gets us some of the lines in the introduction.

Only after reading a good amount of JC and returning to the introduction could I really see some of the hints and warnings Ware drops both the experienced and inexperienced comic reader about reading his text. This helps make it hilarious, but also seems to reveal some of the aspects Ware was more than aware of (and there’s a pun) when constructing the book. So, now I leave it to you as my word count just keeps increasing:

Is Section 4 another warning, but this one for non-comics readers? Or is it just another joke? What else does it tell us about our reading?

Oh Section 5, how I loathed you–or how you made me loathe myself? Anybody else notice the sexism (or at the very least gender bias) that comes after question 1. “Are you male or female? (if b [female], you may stop. Put down your booklet. All others continue”?

Or is he getting at something else here? Like perhaps that a female comic fan wouldn’t have any of these issues of self-hatred and distant daddies that apparently all comic fans (or maybe just Ware himself) have? What does the instruction that women not take the test mean?