A recent Forbes article reported that even though Radiohead is letting listeners decide how much to pay for the band’s new album, In Rainbows, it is briskly being downloaded through bitTorrent. So, fans can get the album legally for free, but many are still downloading pirated copies. In the first week of its release, Forbes reports, In Rainbows was downloaded nearly half a million times illegally, while 1.2 million copies were “paid” for through Radiohead’s online store.

This brings me to my own dilemma. An avid Radiohead fan myself, a few days ago I went to the album’s website, intending to “buy” it.

But I balked.

How much should I pay, I wondered? I wanted to support the band, but what if I didn’t like the album? It even crossed my mind that perhaps the band was “giving” the album away because in their own opinion it wasn’t worth money. Not being charged a specific amount made me question the album’s inherent value. If I pay 99 cents for the latest Britney Spears single, I know that I’m getting less than a dollar’s worth of music (far less, in fact). But with Radiohead there is no price barometer telling me how valuable their music is.

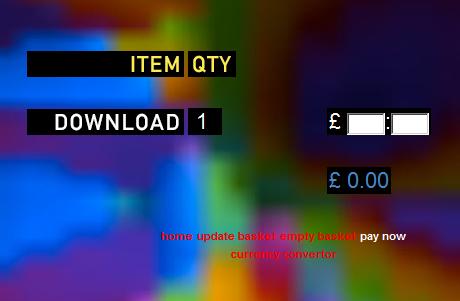

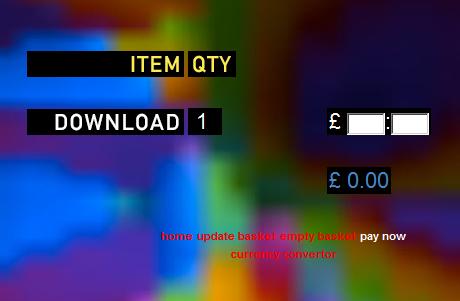

Furthermore, the online store’s interface forces you to consciously decide to pay nothing for the album. You can’t simply visit the website and download the songs. Rather, you add the album to your cart and then at checkout, you must type how much you want to pay (see the screenshot below). Do you type a zero? A one? A ten?

And here’s where a strange thing happened to me: I felt guilty putting in a zero and paying nothing. And here’s the even stranger thing, which the Forbes article presaged: I closed the In Rainbows website without buying the album, neither for nothing nor for something and instead went to my favorite bitTorrent site. There, I saw the album (listed in the top 100 downloads) and was not faced with the decision to pay nothing or something for the album. The illegitimate download would happily free me from such dilemmas.

And here’s where a strange thing happened to me: I felt guilty putting in a zero and paying nothing. And here’s the even stranger thing, which the Forbes article presaged: I closed the In Rainbows website without buying the album, neither for nothing nor for something and instead went to my favorite bitTorrent site. There, I saw the album (listed in the top 100 downloads) and was not faced with the decision to pay nothing or something for the album. The illegitimate download would happily free me from such dilemmas.

This is what I’m saying: the prospect of downloading an illegal copy of In Rainbows made me feel less guilty than going to Radiohead’s site and admitting to the band that I was going to pay nothing for the album.

But then I balked again.

What if, I wondered, the bitTorrent version wasn’t exactly the same as the official downloadable version? What if it were corrupted, or transcoded to a lower bitrate by some anti-piracy zealot? And what about my goal of supporting the band?

So, I closed the bitTorrent website and ended up not downloading anything that day.

A few days later I came up with my solution: I downloaded a legal copy from the official online store and paid nothing for it, vowing that after a handful of listenings to the album I would place a monetary value on the album, revisit the online store, and buy another copy of the album, this time paying real money for it.

In the software world, this is the shareware, or trialware model of pricing, and I’m surprised that it’s taken so long for the music world to try out this model of distribution.

Now, I wonder what an economist would say about my Radiohead legal/illegal/guilty/guilt-free dilemma?