This is the scariest freaking business I’ve read in a long time: a computer science student who had created an online generator for fake boarding passes–solely to point out how ludicrously ineffective airport security is–has been visited several times by the FBI, most recently, with a 2am warrant that allowed the Bureau to seize every single piece of tech in the student’s home. (See a scan of the warrant at BoingBoing).

The kid (he’s 24 years old) is simply highlighting that TSA airport security is “security theater”–providing the illusion of security while actually not protecting anything or anyone. Anybody can print their own online boarding pass and use it to get past gate security (as Andy Bowers illustrated in Slate nearly two years ago); and anyone can easily use two boarding passes to not only get past security, but to board the plane under a false ID.

What’s most amazing is that Soghoian is simply revealing flaws in a system that desperately needs fixing. But the federal government is treating him as a terrorist.

Who’s to say that millions haven’t already printed their own fake boarding passes and done what Soghian is only suggesting?

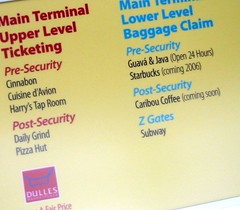

Who’s to say that I, who travel every week from Charlotte to Dulles International Airport, haven’t used Photoshop to doctor an online boarding pass copied from usairways.com to get through security?

I have.

It’s simple, and any idiot can do it.

You take a screenshot of your real boarding pass (right before you print it) (and most airlines allow you to “check in” online, meaning you can call up your boarding pass right in your web browser). And then you edit that screenshot in Photoshop. Substitute your seat assignment, your flight number, whatever. As long as it looks vaguely like US Airways real online boarding pass, you can get right through security.

I did this.

Even though I was a paying customer and had a real boarding pass, I generated a separate fake one. I forged one. Just to test the system.

I got through.

I boarded and flew and landed home.

Now I’m worried. Is the FBI going to come after me? Seize my computers and flash drives and scanners and printers? I did what the terrorists could do. Does that make me an enemy of the state? I broke federal law (DHS Code Title 49, Volume 8; October 1, 2004 rev. [Page 302]. I knowingly lied to a federal official. Security fraud. I committed it.

Or did I?

What if I didn’t print a fake boarding pass. What if I only thought about it. What if I’m lying right now. Who’s to say that I haven’t printed fake boarding passes. Who’s to say that I have.

My lips are sealed.

Except they’re not.

I did this and you should too.

A few days ago I

A few days ago I