Keyne Cheshire, my friend and Classicist extraordinaire has translated Sophocles’ Women of Trachis into an American Western, The Passion of Herman Kilman. The chorale pieces of the play will be performed tonight, live, for the first time ever. Imagine: Hercules, son of Zeus, transformed into Herman Kilman, son of God… [More Information | Full-size PDF]

Keyne Cheshire, my friend and Classicist extraordinaire has translated Sophocles’ Women of Trachis into an American Western, The Passion of Herman Kilman. The chorale pieces of the play will be performed tonight, live, for the first time ever. Imagine: Hercules, son of Zeus, transformed into Herman Kilman, son of God… [More Information | Full-size PDF]

Tag: Music

Michael Jackson and Cultural Relevance

Amid the 24-hour barrage of “news” about Michael Jackson’s death last week, I tweeted, a bit tongue-in-cheek, this question: Is anybody besides me willing to argue that The A-Team was more culturally significant in the eighties than Michael Jackson? My friend Adam wondered whether I and other skeptics were minimizing Jackson’s cultural impact, especially when you consider his record sales, both in the eighties and now, with the spike after his death.

As I commented on Adam’s post (and here comes my entire comment, with revisions), my tweet was half-cocked hyperbole, aimed at the even more hyperbolic coverage of MJ’s life and death. For example, despite the already sanctified media myth, MTV did in fact play music videos from black musicians before Jackson came along.

The man was extremely talented and, for a while, extremely savvy with his image and marketing. I can’t deny that in terms of record sales, Michael Jackson is and will remain a brand name to be reckoned with, but I don’t want to mistake popularity for relevance, or celebrity for significance. MJ is definitely an icon, but he’s also a bit of an empty signifier, a blank page we can project almost anything onto. (Something he no doubt encouraged throughout his career.)

My A-Team reference was a bit facetious, but in some sense, absolutely true for me on a personal level (just as my 5th grade soccer teammate John Booth’s U2 tweet, also mentioned by Adam, was true for him). Of the 12,000 or so tracks in my music collection, exactly one features Michael Jackson (“ABC” by the Jackson Five). Both now and in the eighties the man simply wasn’t on my radar screen (nor were the other titans of eighties pop, Madonna or Prince). Perhaps I am simply pop-musically tone deaf — I’ve never had a Jackson ohrworm. In contrast, I never missed an episode of The A-Team in the eighties, and when I go back and rewatch the show, I have to say that there’s more going on in any single A-Team episode, politically, economically, racially, and historically speaking, than in any MJ song or video.

Finally, I’m not qualified to psychoanalyze MJ’s life (I doubt anyone is), but I think a case could be made that Jackson himself was insecure about his own relevance. This explains why he sought to attach himself to the two greatest musical phenomena of the 20th century that preceded him: The Beatles, by outbidding Paul McCartney in 1984 for the rights to the Lennon-McCartney song catalog; and Elvis, by marrying Lisa Marie Presley ten years later in 1994, thus becoming Elvis’s posthumous son-in-law.

In Jackson’s mind, these earlier musicians were talismans, whose aura might burnish his own (in his mind) uncertain image.

Long Live Rock: Eric Andersen

Eric Andersen, The Tin Angel, Philadelphia, March 1999

Some concerts I remember only who went with me. Some concerts I forget because of who went with me. This show was neither, simply a moving performance I saw with some friends from grad school who are more or less out of my life, though not in any kind of sad way.

I discovered Eric Andersen by luck, browsing the central public library in downtown Cincinnati, summer of 1993, its reading areas dominated by stale, old, sleeping men. I saw this unfamiliar CD in the folk section, the album cover an arresting image of this grim, gaunt man, his face haunted, his eyes dark pools of regret. I took the CD home with me, and I didn’t immediately fall in love with Ghosts on the Road, not at first, but something about the songs compelled me to listen again, and again. The first track that finally pulled me in was “Belgian Bar,” a song that I suddenly realize has influenced my own travel writings, recalling those chance encounters, moments talking to a stranger, that linger in our memories, wisps of magic never fully realized.

I discovered Eric Andersen by luck, browsing the central public library in downtown Cincinnati, summer of 1993, its reading areas dominated by stale, old, sleeping men. I saw this unfamiliar CD in the folk section, the album cover an arresting image of this grim, gaunt man, his face haunted, his eyes dark pools of regret. I took the CD home with me, and I didn’t immediately fall in love with Ghosts on the Road, not at first, but something about the songs compelled me to listen again, and again. The first track that finally pulled me in was “Belgian Bar,” a song that I suddenly realize has influenced my own travel writings, recalling those chance encounters, moments talking to a stranger, that linger in our memories, wisps of magic never fully realized.

Soon I was in captivated by another song on the album, “Irish Lace,” one of the saddest songs I’ll ever know. Andersen’s mournful liner notes describe “Irish Lace” as about two women. One lives not too far away and though she is still around you could say she has gone. The other has long departed this world but I couldn’t say she’s ever left.

I don’t remember if Andersen performed either of these songs that night in 1999, but it didn’t matter. The concert was splendid, full of Andersen’s reminisceces of Philly in the sixties and other American singers — Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton, Bobby Dylan, Townes Van Zandt — on the vanguard of the progressive folk scene. But even with these stories, the concert was not about seeing a relic, but a troubadour who’s seen something of it all. Live, Eric Andersen was more lanky than gaunt, with a touching sense of humor that betrayed none of the melancholy that first drew me to him.

Eighteen months later I was to see Andersen again, but by then, everything had changed.

Long Live Rock: Elliott Smith

The Black Cat, Washington, D.C., September or October 1998

I’ve been doing this concert series on and off for two years now, and a chance encounter with a bootleg recording of Elliott Smith performing John Lennon’s “Jealous Guy” at the Black Cat club cracked open a forgotten memory, a forgotten concert.

In 1998 I saw Elliott Smith at the Black Cat, and I saw him cover “Jealous Guy.” But the performance I saw was not the live version you can find online, generally regarded as the best bootleg concert ever of Smith. That’s the April 17, 1998 show at the Black Cat. I don’t know the exact date, but memory and circumstantial evidence tells me that the concert I saw at the Black Cat was in the fall of that year, late September or maybe October.

No record of that concert exists.

I googled my heart out, scouring the web and local newspapers for a shred of proof that Elliott Smith was at the Black Cat twice in 1998, once when the widely circulated bootleg was taped, and once when I saw him.

Nothing.

It’s as if the show never happened.

I know it was the fall of ’98 because I was no longer living in D.C. and I made a special trip down from Philadelphia to see the show with ██████. A special trip after we had already fallen halfway apart. By this point, every conversation left us, in ██████’s words, gutted.

But we had the tickets, we had the plans, we had the Amtrak schedule, we had it all, and we went through with the concert. Back then the Black Cat was in the middle of a desolate strip of 14th Street. Whole Foods hadn’t been built, and gentrification was a word that only flittered across the pages of the City Paper, a word we laughed at in Logan Circle, when we saw the junkies and dealers come out as night fell, their needles sharp, their eyes hungry.

The concert that ██████ and I saw — unlike the gentle bootleg acoustic April concert — was hard-edged, sharp, maybe even brittle. I don’t think Elliott Smith even brought his acoustic guitar. It was all electric, backed up by the opening act. I don’t know their name, but even if I hadn’t forgotten it, it would have been forgettable. When someone from the audience shouted out “Angeles” as a request, Smith laughed sardonically and mumbled something about that song being impossible to play.

It was ██████ who turned me onto Smith. She had a knack for finding tortured, fated musicians. She adored Jeff Buckley, who drowned while we were together. She was devoted to Morphine, whose lead singer died just after we fell apart. And of course, she found consolation in Elliott Smith’s introverted lyrics, his dark view of the world, his bad haircut.

I guess I must sound hurt or angry, and I guess I probably am. I don’t know whether I’m angry at Elliott or ██████. After the concert, after that night, I never saw either one again, though I sometimes heard and read their words, on the phone, in email, on CD liner notes.

Elliott Smith hung around for five more years, and that’s more than I can say for ██████. She’s around, but she didn’t hang around.

Ten years have past, and somewhere along the way I had forgotten that show. Most times I forget ██████ too. But every so often, when I’m random shuffling through ten thousand songs, I hear Smith’s “Baby Britain,” and a lyric that reminds me of haunted, frightened ██████, who, in the end, I hope has found her way: “You’ve got a look in your eye / when you’re saying goodbye / Like you want to say hi.”

Elliott Smith, “Jealous Guy” (Black Cat, April 17, 1998)

Elliott Smith, “Baby Britain” (End Sessions, February 22, 1999)

Pop Apocalypse: Shearwater’s “Rooks”

I’ve always been obsessed with end-of-the-world scenarios, from the original 1968 Planet of the Apes to Cormac McCarthy’s 2007 novel, The Road. I’ve tried to intellectualize my lifelong fascination, even teaching courses on Apocalyptic Literature. But no matter how many fancy words I use in my courses (“a posteriori apocalypticism,” “stigmatized knowledge,” “escalation ladder”), I cannot fully explain why I am drawn to these bleak tales of catastrophe and suffering.

Just yesterday I realized that my obsession with the apocalypse extends beyond literature and film into the realm of music. In fact, I can clearly recall specific periods in my life and the apocalyptic song that was on my life’s soundtrack at the time. Not counting REM’s “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine)” — a predictable contender on any doomsday playlist — here are the songs on my Armageddon song list:

- In the early nineties it was “The Road to Hell” from Chris Rea’s Road to Hell

- Later in the nineties it was Leonard Cohen’s “The Future” from the album of the same name (“It’s lonely here / there’s no one left to torture”)

- In the days and weeks and months after 9/11 it was “The Dead Flag Blues” from Godspeed You! Black Emperor!’s f#a#∞ (“We’re trapped in the belly of this horrible machine / and the machine is bleeding to death”)

- And now, the song that prompted this reflection, what I’ve been listening to obsessively, is “Rooks” from Shearwater’s Rook

With the song’s haunting arpeggios and singer Jonathan Meiburg’s resonant falsetto, “Rooks” is at once unnerving and beautiful. The lyrics suggests that the End draws nigh, and there’s nothing we can do about it.

With the song’s haunting arpeggios and singer Jonathan Meiburg’s resonant falsetto, “Rooks” is at once unnerving and beautiful. The lyrics suggests that the End draws nigh, and there’s nothing we can do about it.

Or rather, there’s nothing we want to do about it.

It not so much apathy we seek in the face of the disaster, but obliviousness: “The ambulance men said there’s nowhere to flee for your life / so we stayed inside / and we’ll sleep until the world of man is paralyzed”

Listen to “Rooks” by Shearwater:

Thoughts on Ben Folds’ “Still Fighting It”

My friend Adam over at Random Thoughts Escaping posted the Ben Folds’ video of “Still Fighting It,” along with some thoughts about fatherhood.

I’ve always loved “Still Fighting It,” which got heavy rotation on WXPN when the song came out. I’d never seen the video before. I found it quite touching, despite wanting to resist the sappy father-son footage.

Now that I’ve finished watching it, though, I can phase shift back to my ice-hearted self, and ask this critical question: Why don’t my home movies look like that?

I guess because I shoot with video and not film.

And I don’t have a crew.

Or a baby grand piano.

Or a beach.

But…I do have the kid, and that’s what counts.

Long Live Rock: The Tragically Hip

Toledo Zoo Amphitheater, June 1996

The zoo is a crazy place for a rock concert, but for the Tragically Hip, this Depression-era amphitheater was perfect. And this was years before Gord Downie sang about Gus, the polar bear in Central Park (In Between Evolution, 2004). I like to think that the Toledo Zoo was his initial inspiration for this later polar bear song (“What’s troubling Gus / Is it nothing goes quiet?”). Anyone who has seen the Hip in concert, or heard Gord Downie on one of his solo shows, knows that he improvises extended monologues during instrumental breaks in the songs. On this particular night in June, 1996, probably during “New Orleans Is Sinking,” Downie went on a long surreal rant about bored polar bears panting in the sun in the American midwest, an improv piece evidently inspired by his pre-concert walk around the zoo. I think in this same monologue Downie riffed on dolphins too, talking about how the artist dolphins never swam with the rest of the pod.

I went to the concert with Scott, and maybe he remembers some of the monologue too. The Hip was the only live show I saw with Scott, though he and I saw dozens of movies together. I can’t remember how I got Scott hooked on the Tragically Hip, but I did. A month or two after the concert, when I moved away from Toledo, Scott surprised me with the Hip’s rare self-titled 1987 debut CD. By 1996, with moody songs like “Nautical Disaster” and “Springtime in Vienna,” the Hip had moved light years beyond “I’m a Werewolf, Baby.” How could they not?

As an aside that doesn’t fit in with the usual nostalgic tone of all my concert posts, I have to say that the Hip’s online presence is remarkably rich, a model of what a Web 2.0 rock band should look like. In true “Here Comes Everybody” fashion, the site combines Hip-produced content with fan-generated media. Every set list for every show ever is online — here’s the set list for the 1996 Toledo Zoo show. And fans can add their own concert stories in the “Hip Story Project,” which is essentially a digital archive open to everyone, much like the online collections my neighbors at the Center for History and New Media design.

Funny thing, though, I am not going to post my story — this story here — in the Hip’s archive. It belongs to me and my own collection of concert memories. Ultimately these stories are not about any particular band, or even the concert experience, but something much more intangible. The past. And not just any past. My past.

Long Live Rock: Dougie MacLean

The Ark, Ann Arbor, circa 1996

Another concert with Tim, who was in grad school at Michigan by this point. Dougie was fantastic — The Ark is an intimate venue, and as I remember it, we were sitting just a row or two from the stage. I watched transfixed as Dougie tuned his guitar differently for each song, taking only seconds to go from a standard EADGBE to a rich open tuning like DADABD.

What really stands out in my mind twelve years later is how I came to the music of Dougie MacLean in the first place, through a series of acquaintances in college whose names I have trouble even recalling. At the end of the line was Wendy, whose name I do recall, though I don’t know what her last name is these days. On a mix tape I must still have, tucked away in some shoebox — though with no means to play it — she had included “Ready for the Storm” and another MacLean song, and I’m having trouble just now remembering which one. Maybe “Singing Land” or “Caledonia.” But definitely “Ready for the Storm.” I’ll never forget how blown away I was when I heard the song for the first time. It was even more powerful when I heard Dougie perform it live a few years later, but some of that power must have come from the bailfuls of nostalgia that swamped me at the time.

Going back a few years, Wendy had dubbed the two songs from a mix tape of her roommate’s, a zoology major named Heidi. I want to say Heidi Michaels was her name, but I can’t say for sure. Google doesn’t help in this regard. She was supposed to have gone off to grad school to study wolves, but I don’t know that she did.

Heidi’s mix tape was made by a friend of hers, a sometime suitor named Colin. I want to say Colin’s last name was Michaels too, but that can’t be right. This is where the trail really goes cold. I don’t think Colin and I ever said much to each other. The odd thing is that one spring break, 1992 it must have been, a van full of these people I’m naming drove to Hilton Head, where Colin’s family had an empty condo waiting for us on a golf resort. Who all went on this trip I’m having trouble remembering: Wendy, Heidi, Colin, me, and some other people too. There was one of Heidi’s friends, named OT, which was short I guess for Othelia. She moved to Brazil after graduation. I seem to remember this. To work in a pizza parlor with her older sister, who was married to a Brazilian man? I think I’ve got that right.

The beach at Hilton Head was usually too cold for swimming, and none of us golfed. Heidi and Colin mostly went birding.

Funny, as I wrote that last sentence I’m listening to a Dougie MacLean CD I bought years later, and the song playing right now is “High Flying Seagull.”

Anyway, so all these people are gone from my life, and even in 1996 at the concert with Tim, they were gone then too.

Tim and I are still in touch. And Dougie’s still around too. I see he’s going back to The Ark in Ann Arbor this September. If I were a few hundred miles closer I’d try to see him again. It’s the closest he comes to North Carolina. Mostly he’s in Scotland. Everyone is in some place, aren’t they?

Long Live Rock: The Indigo Girls

I’m not quite finished with the concerts of the nineties yet, though from here on out I’ll be jumping around chronologically, as I remember the shows. And here is one I can’t believe I almost forgot:

Indigo Girls, Toledo, 1995

Two things I remember about this show, maybe three.

(1) I went with Tim, my closest friend in Toledo, an alien city at the time. Tim was basically the guy who nudged me on to graduate school after I roosted for a few years as a high school teacher.

(2) This was the Indigo Girls’ Swampophilia tour, the first CD of theirs that I didn’t buy, and never did buy, and I don’t know why, because it’s great.

(3) The show was at the Masonic Complex, a great indoor venue, and I just love saying the name, Masonic Complex. It’s like something Freud would have to diagnose.

(4) Tim and I later saw La Boheme at the Masonic Complex (Masonic Complex, just say it with me). I don’t think the musical qualifies as a rock concert, but it’s worth mentioning anyway, because there’s another great name involved here, a student of mine who I remember seeing at the show, his nose buried in a book the whole time. This would be a troublesome nerd I had a great fondness for, Alaric. If Alaric didn’t have Asperger’s Syndrome, he should have.

So that’s four things I remember, not three. What did the Indigo Girls sing? I have no idea, but I’m sure “Closer to Fine” was in there, the only song of theirs I ever mastered musically and vocally, only because Matt Sutter had told me a few years earlier that the Indigo Girls were the future of alternative music. (And we were in, at the time, the home of the Future of Rock and Roll, 97X…)

Long Live Rock in the New Millennia: Mojave 3

A long time back I began a series of posts about the different live concerts I’ve seen since the eighties. A student of mine who happens to be a Glen Phillips fan dug up an old post about a Toad the Wet Sprocket concert in the early nineties. It got me thinking that I never did finish my concert reminisces. So, here I am, picking up approximately where I left off.

Mojave 3, North Star Bar, Philadelphia, 2001

I first heard Mojave 3 in a coffeshop on Pine Street — the Last Drop Coffeehouse I think. I was there with John, and Mojave 3 was playing softly on the shop’s stereo. This was back when Napster was a revelation operating under the radar, and I went back to my apartment and downloaded whatever Mojave 3 songs I could find. I fell in love with “A Prayer for the Paranoid.”

A few months later Mojave 3 was live in Philly, at the North Star Bar. I went with Matt and Stephanie, about the oddest trio you’d ever seen. But then, put Stephanie with any two people and you’d end up with an odd trio.

I remember Matt saying that no band deserves to sing such gorgeous songs and look so gorgeous on top of that. And they were gorgeous. I smuggled a pint glass out of the bar. Seven years later it’s the only memento I have from that evening, the only memento from that entire spring.

My life on Random Play

So my ancient 30gb MP3 player broke, and the only buttons that work now are the volume controls and the “Random Play” button. I’m going to milk this brick-like, nearly bricked player for all it’s worth, and so I’m now cycling through the 8,000 songs in the random play, and I’m hearing things I haven’t heard for years.

One immediate observation:

Something really pisses me off about Jack Johnson’s voice. Am I the only one? It actually hurts my ears. I don’t even know why I have him on here. Every time his ingratiating, insouciant voice comes up I frantically press the “next” button–until I remember it doesn’t work anymore.

This is going to be a long 500 hours of music…

Why do I feel guilty paying nothing for Radiohead’s “In Rainbows”?

A recent Forbes article reported that even though Radiohead is letting listeners decide how much to pay for the band’s new album, In Rainbows, it is briskly being downloaded through bitTorrent. So, fans can get the album legally for free, but many are still downloading pirated copies. In the first week of its release, Forbes reports, In Rainbows was downloaded nearly half a million times illegally, while 1.2 million copies were “paid” for through Radiohead’s online store.

This brings me to my own dilemma. An avid Radiohead fan myself, a few days ago I went to the album’s website, intending to “buy” it.

But I balked.

How much should I pay, I wondered? I wanted to support the band, but what if I didn’t like the album? It even crossed my mind that perhaps the band was “giving” the album away because in their own opinion it wasn’t worth money. Not being charged a specific amount made me question the album’s inherent value. If I pay 99 cents for the latest Britney Spears single, I know that I’m getting less than a dollar’s worth of music (far less, in fact). But with Radiohead there is no price barometer telling me how valuable their music is.

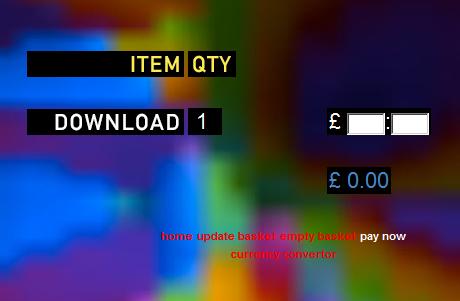

Furthermore, the online store’s interface forces you to consciously decide to pay nothing for the album. You can’t simply visit the website and download the songs. Rather, you add the album to your cart and then at checkout, you must type how much you want to pay (see the screenshot below). Do you type a zero? A one? A ten?

And here’s where a strange thing happened to me: I felt guilty putting in a zero and paying nothing. And here’s the even stranger thing, which the Forbes article presaged: I closed the In Rainbows website without buying the album, neither for nothing nor for something and instead went to my favorite bitTorrent site. There, I saw the album (listed in the top 100 downloads) and was not faced with the decision to pay nothing or something for the album. The illegitimate download would happily free me from such dilemmas.

And here’s where a strange thing happened to me: I felt guilty putting in a zero and paying nothing. And here’s the even stranger thing, which the Forbes article presaged: I closed the In Rainbows website without buying the album, neither for nothing nor for something and instead went to my favorite bitTorrent site. There, I saw the album (listed in the top 100 downloads) and was not faced with the decision to pay nothing or something for the album. The illegitimate download would happily free me from such dilemmas.

This is what I’m saying: the prospect of downloading an illegal copy of In Rainbows made me feel less guilty than going to Radiohead’s site and admitting to the band that I was going to pay nothing for the album.

But then I balked again.

What if, I wondered, the bitTorrent version wasn’t exactly the same as the official downloadable version? What if it were corrupted, or transcoded to a lower bitrate by some anti-piracy zealot? And what about my goal of supporting the band?

So, I closed the bitTorrent website and ended up not downloading anything that day.

A few days later I came up with my solution: I downloaded a legal copy from the official online store and paid nothing for it, vowing that after a handful of listenings to the album I would place a monetary value on the album, revisit the online store, and buy another copy of the album, this time paying real money for it.

In the software world, this is the shareware, or trialware model of pricing, and I’m surprised that it’s taken so long for the music world to try out this model of distribution.

Now, I wonder what an economist would say about my Radiohead legal/illegal/guilty/guilt-free dilemma?

A sound I love

Here’s a sound I love: biking over a wood bridge and hearing the planks knock together as my tires roll over them.

Long Live Rock, the Nineties, Part IV

10. The Moody Blues (1994?, Blossom Music Center)

Suddenly it was the eighties again.

Long Live Rock, The Nineties, Part III

Hothouse Flowers / Ziggy Marley and the Wailers / Midnight Oil (1993, Cleveland)

A triple bill. An absurdly mismatched triple bill. I went for Hothouse Flowers, Wendy went for Midnight Oil. We both grooved to the Wailers, although reggae really wasn’t my thing back then. I guess it still isn’t. Peter Garrett was huge. At least two heads taller than anybody else on stage. He’s in the Australian Parliament now. He’s probably the tallest man in the room whenever they meet. That’s got to count for something, in rock and politics both. Bono on the other hand is short, I think, probably too short for a serious career in electoral politics. I guess you can still try to save the world, even when you’re short, if you operate outside of elected positions.

But in 1993, Garrett was still a rock singer, and Bono, I don’t even know why I’m talking about him.