In 2009, my brother and I self-published “The End of Gath,” a graphic novel trilogy. It was based on an idea (a dream, really) my brother had that grew into a Steampunk/science fantasy story. Being a graphic artist, he had the images in his mind, but not necessarily a fleshed-out narrative. I’ve written some fiction – short stories, one novel perpetually in revision – and have critiqued and edited many works by friends over the years. My brother asked me to assist with the written part of his three-part tale, and I jumped at the opportunity.

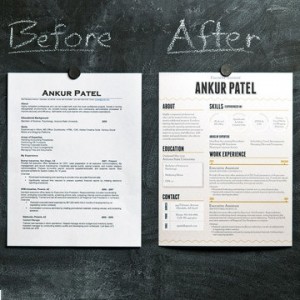

It was an interesting project – I had to write with the idea that the visuals would cohabit the pages, but for the most part, those visuals didn’t exist when I wrote my bits. We constructed it not in standard comic panel structure, but as what I consider a truer version of the term “graphic novel”: large visuals interspersed with blocks of text. My brother created illustrations that were imaginative and beautiful to look at. We critiqued and suggested changes to each other’s contributions. After a number of years of work, we had a finished product we both loved. Others seemed to love it, too – especially the pictures. Not surprisingly, they were the first things anyone noticed about the book … sometimes the only things people noticed. There are words there, I wanted to say, if only you’d bother to read them. Damn. Had I spent long hours of work and thought on a glorified picture book?

The answer is no. It’s a good story, and I’m proud of my part in creating it, adding much to my brother’s original framework. The book might have benefited from making the text stand out more vis-a-vis the illustrations (larger type size, different font, etc.). But I am sold on the graphic novel format as a distinct and effective way to tell a story, communicate ideas, etc. I am sure there are people who would never have picked up that book, never have viewed more than a page or two without the illustrations. The visuals draw people in, make the text come to life, enhance it in so many ways.

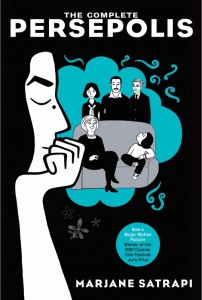

As such, I don’t view graphic novels or the comic panel format as any kind of “dumbing down” or oversimplification of a given text. Rather, it is another way of communicating and enhancing the author’s message. And, just as video games demand and develop certain skills that are beneficial to learning, graphic novels and comics, as Scott McCloud points out, ask that readers use their imaginations and play an active role in their understanding of the story told. This is due, in part, to the manipulations of temporal and spatial elements that McCloud discussed. But it is also seen in the way writers may illustrate a story to show an elaborate analogy and help the reader make connections. For example, Art Spiegelman, in his devastating two-part work, “Maus,” tells his father’s Holocaust story and its emotional and psychological aftermath through the depiction of the European Jews as mice and the Nazis as cats. Readers may, after a while, get so involved in the story that they almost forget the characters are shown as animals, but the subtext of hunters and prey remains – one that can easily be understood by people of different eras, ages and backgrounds.

I hope the use of graphic novels and comics grows in schools and in the literary world. We should use every tool at our disposal to enliven learning, reading and writing for our students – and everybody else, for that matter.