The Expressive Work of Spaces of Torture in Videogames

At the 2014 MLA conference in Chicago I appeared on a panel called “Torture and Popular Culture.” I used the occasion to revisit a topic I had written about several years earlier—representations of torture-interrogation in videogames. My comments are suggestive more than conclusive, and I am looking forward to developing these ideas further.

Today I want to talk about spaces of torture—dungeons, labs, prisons—in contemporary videogames and explore the way these spaces are not simply gruesome narrative backdrops but are key expressive features in popular culture’s ongoing reckoning with modern torture.

There are many videogames I could talk about today. Recent offering such as Grand Theft Auto 5 and the latest Tomb Raider reboot are saturated with acts of cruelty and physical abuse that would fit many definitions of torture. Older games such as Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic and the Splinter Cell franchise make torture integral parts of the game. For the sake of brevity I’ll mention several representative examples and spend a bit more time with one specific game, 2012’s Dishonored by Arkane Studios.

First I want to be clear about what I mean by torture. There are legal definition we can use. One comes from the United Nations Convention against Torture, to which the United States is a signatory. According to this international agreement, torture means intentional infliction of severe physical or mental pain or suffering (Kreimer 190). This concept of torture was directly applied to videogames in a California law signed in 2005 by then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The law would have banned the sale of violent videogames to minors, but it was repealed in 2007 by the Ninth Circuit Court. Nonetheless, its legal specificity regarding the definition of torture in videogames is worth mentioning. According to the California law, torture includes “mental as well as physical abuse of the victim. In either case, the virtual victim must be conscious of the abuse at the time it is inflicted” (“Violent Video Games,” 1746E).

In an earlier research project influenced by Elaine Scarry’s work I parsed the language of this law, arguing that its insistence that the virtual victim be conscious arose from the goal of torture, which is to produce a confession, a recantation, or, in the case of counter-terrorism operations, the acquisition of information from the victim, what the CIA would euphemistically call “intel.”

You can see this dynamic at work in videogames set against the backdrop of the war on terrorism. Here is Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell, in which the player-character interrogates a guard by choking him. The interrogation commands only appear when the non-playable character has valuable information. The player knows simply by virtue of the game interface whom to torture and when.

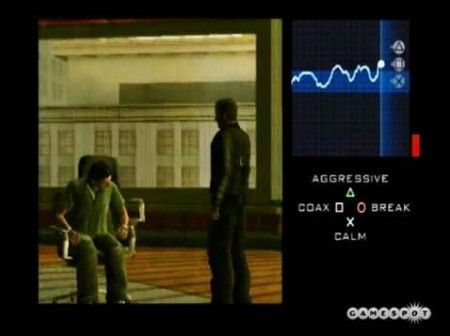

A more fully developed version of torture-interrogation appeared in 24, a Playstation 2 game based on the popular FOX television series. Here torture appears as a mini-game, in which the player—acting as Jack Bauer—adopts several approaches to his interrogation—a calm “Good Cop” style, an aggressive “Bad Cop” approach, and so on.

The player’s goal is to combine these various approaches in order to keep the virtual victim in what the game calls a “cooperation zone”—that’s the blue band up on the screen. The longer the suspect remains in the cooperation zone, the more information Bauer extracts from him.

The correct sequence of tactics culminates with Bauer threatening the suspect with a gun aimed at his head, at which point the suspect “breaks.”

Both Splinter Cell and 24: The Game present an idealized—and inaccurate—vision of torture-interrogation. In both games, the player receives intel that is not only useful but useful immediately. In fact, the player cannot proceed in the game without the intel. The logic of these games suggests that torture is winnable, necessary, scientific, and effective.

In short, these games present a kind of procedural rhetoric about torture. Procedural rhetoric is a term that’s becoming increasingly familiar to anyone who studies videogames or other forms of computational media. It’s an idea from Ian Bogost that accounts for the way an argument can be made by a computer model. Instead of describing the way the world works with words—like, say, a realist novel—or depicting the world through images and sound, like cinema, videogames “make a claim about how something works by modeling its processes” (Bogost 2009). So, these games model torture and by doing so, present an explicit claim about the way torture works.

One of the rhetorical arguments these games make about torture for the purposes of interrogation is that it happens in situ, as a makeshift technique improvised on-the-spot at the time of the victim’s apprehension.

One of the effects of this immediacy is that the actual sites of torture in real life are erased. The prison, the detention center, the camp—they all disappear from videogames about terrorism, just as the prisoners in these spaces disappear in real life. This is part of these game’s procedural rhetoric: they model a version of torture-interrogation that eliminates institutional sites of torture, replacing a bureaucratic, systemic structure of containment and abuse with an individualized, heroic quest for the truth.

My paper today is an intervention into this procedural rhetoric. But rather than looking at games that expunge institutional sites of torture from the record, I want to turn to videogames that integrate them directly into gameplay. I’m talking about—depending on the game’s genre—prisons, labs or dungeons.

Roughly speaking, there are two types of games that feature institutional sites of torture. The first type of game is the game of discipline and control, in which the player’s job is to manage a prison or some other space of containment. These games of control rely on an omniscient perspective, the kind many of us are familiar with from simulations like SimCity. The tongue-in-cheek franchise Tropico, in which the player runs a Caribbean island as a power hungry dictator is an example of the game of control. Once you build a prison in Tropico you can enter edict mode, which allows you to arrest any person on the island, at any time.

A more recent game of discipline and control is the crowd-funded Prison Architect by the British game developer Introversion. Still in alpha release, Prison Architect is a Sim-style game in which the player designs and manages a maximum security prison. The game begins with the player tasked with building an execution chamber, complete with an electric chair, which is what you see me buying here.

The second type of game featuring institutional sites of torture are games of confinement and its corollary, escape. If in games of control, prisons are information spaces, which the player navigates through a series of menus and layers, games of confinement and escape use the prison as a treacherous but navigable space. The player assumes the identity of an often unjustly imprisoned inmate, attempting escape under extraordinary circumstances (a research experiment gone wrong, an invasion of demonic monsters, and so on). The survival horror franchises The Suffering and Manhunt are well-known examples of these games of confinement and escape. Portal and Portal 2 also fit this model. Unlike the objective omniscient perspective afforded by games of control, games of confinement tend to be first-person shooters, with a subjective point of view.

Into these two categories of games—manage the prison and escape the prison—I want to add a third category. And these are games where the player, for lack of a better word, tours the prison. That is, the player him or herself is not confined or subject to torture, but is rather passing through a site of institutional torture on his or her way to some place else.

A striking example occurs early in Bethesda’s Skyrim. Making his or her way out of a dungeon at the start of the game, the player must pass through a torture chamber and defeat an imperial torturer. Unlike games such as Splinter Cell or 24 there is little procedural rhetoric about torture at work. Instead, the torture chamber functions expressively. Skyrim makes no claim about how torture works; instead it shows us what torture looks like.

It’s worth recalling Henry Jenkins’ argument that games can tell stories simply through their level design, by embedding narrative cues in the canvas of the game world. Jenkins draws a parallel to the environmental storytelling found in theme parks, where attractions and rides based on stories and films don’t recreate the narrative event so much as they evoke the atmosphere of the fictional world.

By embedding narrative information in the sights and sounds of the mise-en-scene, videogames can, quoting Jenkins, “tap the emotional residue of previous narrative experiences” (Jenkins 2004).

One of the more stunning evocative spaces I’ve encountered in the past year appears in the game Dishonored, by Arkane Studios. The game is set in a plague-ravaged Victorian-like era that’s not cyberpunk so much as it is magical industrialism—with oil from whales powering the economy.

Dishonored opens with the player-character falsely accused of assassinating the Empress of Dunwall and escaping from prison just hours before his execution. The game appears to fall into the confinement and escape category of games. Yet, I’d argue that since the player escapes so quickly from the prison and in fact revisits it later in one of the expansion packs, prisons and dungeons in Dishonored function more as evocative spaces with something to say than as hostile spaces that must be overcome.

Dishonored opens with the player-character falsely accused of assassinating the Empress of Dunwall and escaping from prison just hours before his execution. The game appears to fall into the confinement and escape category of games. Yet, I’d argue that since the player escapes so quickly from the prison and in fact revisits it later in one of the expansion packs, prisons and dungeons in Dishonored function more as evocative spaces with something to say than as hostile spaces that must be overcome.

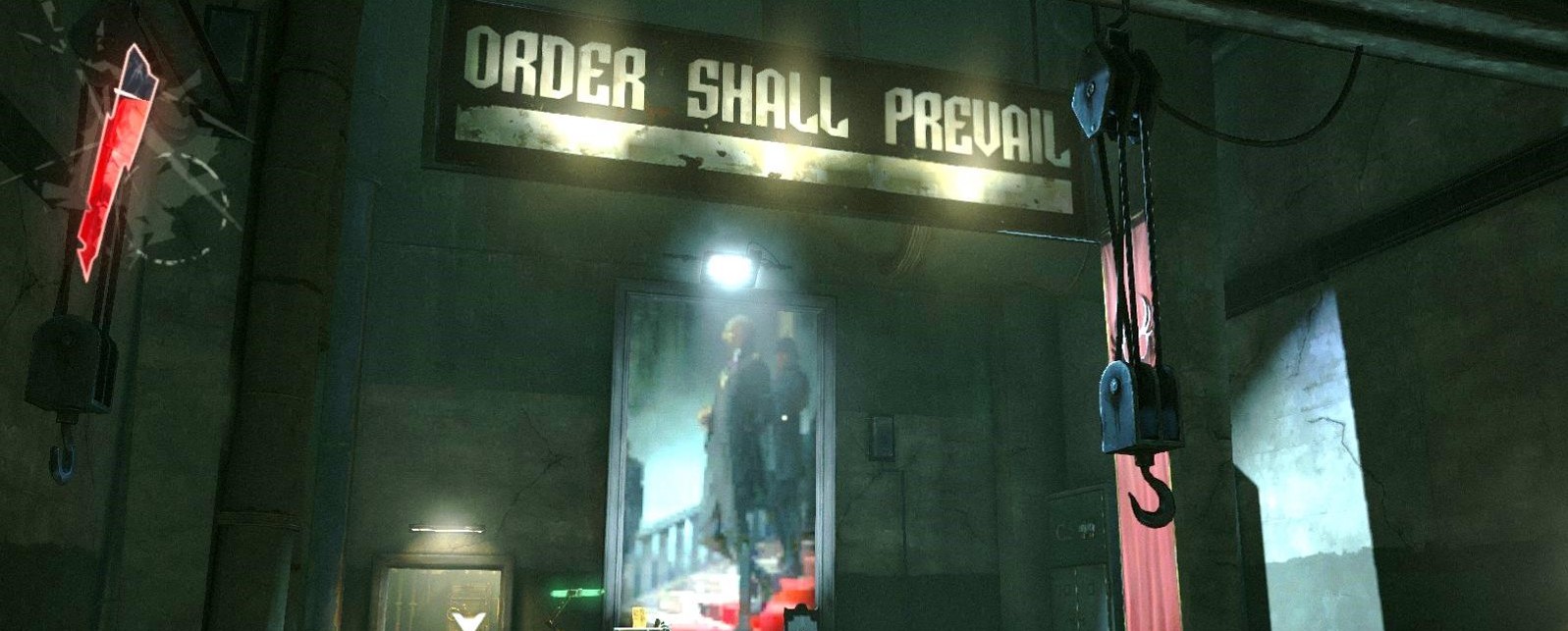

And we see this nearly right away, when the player stumbles upon an Interrogation Room as he or she makes an escape. The room is dimly lit, full of menacing shadows and—important for my argument today—empty of victims or torturers. The room evokes the pain and misery that occurs here without showing it.

The centerpiece of the room is an apparently metal chair with straps and stirrups, a pool of blood at its base. A grate lies to the side of the chair, apparently for quick clean-up.

The centerpiece of the room is an apparently metal chair with straps and stirrups, a pool of blood at its base. A grate lies to the side of the chair, apparently for quick clean-up.

In front of the chair, where the torturer would stand, is a fire pit and a wooden workbench with commonplace tools: a sledge hammer and a gouge.

Overhead hangs a gigantic hook connected to a pulley system. And finally, the front part of the room is dominated by a red banner, the symbol of the theocratic regime that engineered the empress’s assassination and took over the government of Dunwall.

At the front of the room—where the tortured victim would be facing—is a large portrait of the new regent of Dunwall, with an Orwellian slogan overhead.

At the front of the room—where the tortured victim would be facing—is a large portrait of the new regent of Dunwall, with an Orwellian slogan overhead.

All of these details contribute to the expressive power of the space itself. Now, I began this paper suggesting that the way sites of torture appear in videogames says something about popular culture’s engagement with modern torture. So let me offer a few tentative conclusions.

All of these details contribute to the expressive power of the space itself. Now, I began this paper suggesting that the way sites of torture appear in videogames says something about popular culture’s engagement with modern torture. So let me offer a few tentative conclusions.

First, I want to revise the thesis of my earlier research on torture, that suggested a verbal response of some sort was the goal of torture in videogames. Here, with the Nazi-style pageantry and towering portrait, clearly power is on display. Torture is a show. The fact that I calmly explored this room without fear of attack, taking these screenshots as a tourist might photograph interesting monuments, suggests the wanting-to-be-seenness of the torture chamber. On one hand this resonates with the viewpoint that torture is not simply about getting a confession or intel. Torture is about intimidation, a performance of power.

On the other hand, this spectacle doesn’t fit with what we know about modern torture: that it’s increasingly what the political scientist Darius Rejali calls “clean” torture. That is, physically abusive techniques that leave no marks on the victims. Electrotorture, water, ice, and asphyxiation all have “clean” variants. Rejali describes the shift to stealth torture in exhaustive detail in his book Torture and Democracy, and I’ll just highlight two of his overarching points: one, the shift to clean torture is likely due to the increased public monitoring of torture that has occurred since the 1970s; and two, communities treat the victims of stealth torture much differently from victims whose bodies bear physical evidence of their abuse.

Consider the hook and pulley in Dishonored, which evokes the devastating strappado, in which a prisoner is handcuffed behind his back, a hook is placed in the handcuffs, and then hoisted with a pulley system. This is not stealth torture. The hot coals and sledge hammer in the room likewise suggest torture that leaves temporary or permanent damage; Rejali calls these types of torture “scarring techniques.” And again, this is not what modern torture looks like. So here then is my second tentative conclusion: the version of torture evoked in these videogame spaces is—and this might be an unfortunate word choice—nostalgic. Nostalgic for visible pain and suffering.

Even contemporary games that graphically depict torture rather than architecturally evoke it emphasize scarring techniques. Some of the torture implements at your disposal in Grand Theft Auto 5 are a wrench and a sledgehammer, clearly the tools of a scarring technique.

So what does it mean that videogames are nostalgic for a bygone era of torture? I have no clear answer. Is it that scenic evidence of scarring torture performs necessary narrative work—driving home the brutality of the oppressive regime, justifying the player’s own cruel retaliatory acts? Is it that clean torture—the kind of torture, as Rejali documents, that was pioneered by British, American, and French democracies—doesn’t make for compelling gameplay or evocative level design? Is it that the victims of stealth torture—whose suffering is invisible and who are treated by communities almost as if they weren’t victims at all—is it that those victims of stealth torture are impossible to depict in videogames?

Or is it that videogames as a medium aren’t ready to confront the paradox of torture—that the more we look for it, the better it hides?

Works Cited

- Bogost, Ian. “The Proceduralist Style.” Gamasutra 21 Jan. 2009. Web. 1 Feb. 2009 . <http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3909/persuasive_games_the_.php?print=1>.

- Jenkins, Henry. “Game Design as Narrative Architecture.” First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game. Ed. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004. 118–130. Print.

- Kreimer, Seth F. “Torture Lite, Full Bodies Torture, and the Insulation of Legal Conscience.” Journal of National Security Law & Policy 1 (2005): 187-229. Print.

- Rejali, Darius M. Torture and Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. Print.

- Violent Video Games: Sales to Minors, California State Assembly, 2005-2006 Sess., Part 4, Division 3 Cong. Rec. Section 1746 (2005).

Finally posted my #MLA14 talk. “Sites of Pain and Telling: The Expressive Work of Spaces of Torture in Videogames” http://t.co/IGJfsRC2pH

“In short, these games present a kind of procedural rhetoric about torture.” http://t.co/DwmCjnawFE

Sites of Pain and Telling: The Expressive Work of Spaces of Torture in Videogames http://t.co/CpswfCPh47

Representations of torture in videogames doesn’t fit with what we know about modern torture. http://t.co/IGJfsRC2pH

Video games, torture & procedural-rhetoric*.

http://t.co/hRb6OnSkhP

*Making a claim about how something works by modelling its processes.

Sites of Pain and Telling | SAMPLE REALITY – http://t.co/uoGW2yapvK

[…] The work of torture in video games. Is it immoral to kill video game characters? Video games as ideological […]

“Sites of Pain and Telling: The Expressive Work of Spaces of Torture in Videogames” great piece from @samplereality http://t.co/65kwh00UOf